Kullanıcı:Sp1dey/Çalışma

Mısır | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Yerküre üzerindeki konumu | |||||||||||||

| Başkent ve en büyük şehir | Kahire 30°2′K 31°13′D / 30.033°K 31.217°D | ||||||||||||

| Resmî dil(ler) | Arapça | ||||||||||||

| Ulusal dil | Mısır Arapçası[a] | ||||||||||||

| Resmî din | bkz. Mısır'da din[b] | ||||||||||||

| Demonim | Mısırlı (Arap) | ||||||||||||

| Hükûmet | Otoriter rejim altında yarı başkanlık sistemli üniter cumhuriyet[5][6][7][8][9] | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Yasama organı | Parlamento | ||||||||||||

| Senato | |||||||||||||

| Temsilciler Meclisi | |||||||||||||

| Tarihçe | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Yüzölçümü | |||||||||||||

• Toplam | 1.010.408[13][14] km2 (29.) | ||||||||||||

• Su (%) | 0,632 | ||||||||||||

| Nüfus | |||||||||||||

• 2023[15] tahminî | |||||||||||||

• 2017 sayımı | |||||||||||||

• Yoğunluk | 103,56/km2 (118..) | ||||||||||||

| GSYİH (SAGP) | 2021 tahminî | ||||||||||||

• Toplam | |||||||||||||

• Kişi başına | |||||||||||||

| GSYİH (nominal) | 2023 tahminî | ||||||||||||

• Toplam | |||||||||||||

• Kişi başına | |||||||||||||

| Gini (2019) | ▼ 31.9[17][18] orta · 46. | ||||||||||||

| İGE (2021) | yüksek · 97. | ||||||||||||

| Para birimi | Mısır lirası (EGP) | ||||||||||||

| Zaman dilimi | UTC+2 (DAS) | ||||||||||||

• Yaz (YSU) | UTC+3 (DAYS) | ||||||||||||

| Trafik akışı | sağ | ||||||||||||

| Telefon kodu | 20 | ||||||||||||

| İnternet alan adı | .eg | ||||||||||||

Mısır (Arapça: مصر, romanize: Mısr), resmî olarak Mısır Arap Cumhuriyeti, Afrika'nın kuzeydoğu köşesi ile Asya'nın güneybatı köşesinde Sina Yarımadası'nı kapsayan kıtalararası bir ülkedir. Kuzeyinde Akdeniz, kuzeydoğusunda Filistin'in Gazze Şeridi ve İsrail, doğusunda Kızıldeniz, güneyinde Sudan ve batısında Libya ile komşudur. Kuzeydoğudaki Akabe Körfezi, Mısır'ı Ürdün ve Suudi Arabistan'dan ayırmaktadır. Kahire, Mısır'ın başkenti ve en büyük şehridir. İkinci büyük şehri olan İskenderiye ise Akdeniz kıyısında önemli bir sanayi ve turizm merkezidir. Yaklaşık 100 milyon nüfusuyla Mısır, dünyanın en kalabalık 14'üncü, Afrika'nın ise en kalabalık üçüncü ülkesidir.

Nil Deltası boyunca uzanan Mısır, MÖ 6 ile 4 bininci yıllara kadar dayanan mirası ile en uzun tarihî geçmişe sahip ülkelerden biridir. Medeniyetin beşiği olarak kabul edilen Antik Mısır; yazı, tarım, kentleşme, organize din ve merkezî hükûmet alanlarındaki ilk gelişmelerden bazılarına sahne olmuştur.[20] Yedinci yüzyılda büyük ölçüde İslam'ı benimsemeden önce Mısır Hristiyanlığın önemli merkezlerinden biriydi. Kahire, 10. yüzyılda Fâtımîler'in, 13. yüzyılda ise Memlûk Devleti'ne başkentlik yapmıştır. Mısır daha sonra, 1517 yılında Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun bir parçası oldu ve Kavalalı Mehmed Ali Paşa'nın 1867'de özerk bir Hidivlik kurmasına kadar Osmanlı hâkimiyeti altında kaldı. Ülke daha sonra Britanya İmparatorluğu tarafından işgal edildi ve 1922'de monarşi olarak bağımsızlığını kazandı. 1952 devriminin ardından Mısır'da cumhuriyet ilan edildi ve 1958'de ülke Suriye ile birleşerek Birleşik Arap Cumhuriyeti kuruldu. Bu cumhuriyet 1961'de dağılmıştır. Mısır 1948, 1956, 1967 ve 1973'te İsrail'le birçok silahlı çatışmaya girmiş ve 1967'ye kadar Gazze Şeridi'ni işgal etmiştir. 1978'de Mısır, Sina'dan çekilmesi karşılığında Camp David Sözleşmesi'ni imzalayarak İsrail'i resmî olarak tanımış oldu. 2011 Mısır Devrimi'ne ve Hüsnü Mübarek'in devrilmesine neden olan Arap Baharı'nın ardından ülke uzun süren bir siyasi istikrarsızlık dönemiyle karşı karşıya kaldı. Buna 2012'de Muhammed Mursi'nin öncülük ettiği Müslüman Kardeşler bağlantılı kısa ömürlü İslamcı hükûmetin seçilmesi ve bu hükûmetin 2013'teki kitlesel protestoların ardından devrilmesi de dahil idi.

2014 yılında seçilen ve o zamandan beri Abdülfettah es-Sisi tarafından yönetilen Mısır'ın yarı başkanlık sistemine dayalı mevcut hükûmeti, bazı gözlemci kurumlar tarafından otoriter olarak değerlendirilirken ülkenin insan hakları durumunun zayıf kalmasından sorumlu tutulmaktadır. Mısır'ın resmî dini İslam, resmî dili ise Arapça'dır.[21] Nüfusun büyük bir çoğunluğu, ekilebilir tek arazinin bulunduğu, yaklaşık 40.000 kilometrekarelik Nil Nehri kıyılarına yakın alanlarda yaşamaktadır. Mısır topraklarının çoğunu Sahra Çölü oluşturur ve buradaki geniş alanlarda seyrek yerleşimler gözlemlenir. Mısır'da yaşayanların yaklaşık %43'ü ülkenin kentsel alanlarında yaşamaktadır.[22] Bunların çoğu Kahire, İskenderiye ve Nil Deltası'ndaki diğer büyük şehirlerin yoğun nüfuslu merkezlerine yayılmış durumdadır.

Mısır Kuzey Afrika, Orta Doğu ve İslam dünyasında bölgesel bir güç, dünya çapında ise orta bir güç olarak değerlendirilmektedir.[23] Afrika'nın üçüncü büyük ekonomisi, dünyanın nominal GSYİH açısından 38. ve kişi başına nominal GSYİH açısından 127. en büyük ekonomisi olan, çeşitlendirilmiş bir ekonomiye sahip, gelişmekte olan bir ülkedir.[24] Mısır; Birleşmiş Milletler, Bağlantısızlar Hareketi, Arap Birliği, Afrika Birliği, İslam İşbirliği Teşkilatı, Dünya Gençlik Forumu'nun kurucu üyesi olmakla beraber ve bir BRICS üyesidir.

Etimoloji[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

| |

| |

Tarihçe[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Tarih öncesi dönem ve Antik Mısır[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Nil kıyıları boyunca ve çöl vahalarında kaya oymalarına dair kanıtlar bulunmaktadır. MÖ 10. binyılda avcı-toplayıcı ve balıkçı kültürünün yerini tahıl öğütme kültürü almıştır. MÖ 8000 civarında iklim değişiklikleri veya aşırı otlatma, Mısır'ın pastoral topraklarını kurutarak Sahra'yı oluşturmaya başladı. İlk kabile halkları, yerleşik bir tarım ekonomisi ve daha merkezi bir toplum geliştirdikleri Nil Nehri civarlarına doğru göç etmiştir.[38]

Milattan önce yaklaşık 6000'li yıllara gelindiğinde, Nil Vadisi'nde Neolitik bir kültür kök salmaya başladı.[39] Neolitik çağda, Yukarı ve Aşağı Mısır'da birbirinden bağımsız olarak birkaç hanedan öncesi kültür gelişti. Badâri kültürü ve onun devamı olan Nakada, genel olarak Mısır hanedanlığının öncüleri olarak kabul edilmektedir. Bilinen en eski Aşağı Mısır bölgesi olan Merimda, Badâri'den yaklaşık yedi yüz yıl öncesine dayanmaktadır. Çağdaş Aşağı Mısır toplulukları güneydeki benzerleriyle iki bin yıldan fazla bir süre bir arada yaşamış ve ticaret yoluyla sık sık etkileşim kurmuşlarsa da kültürel olarak birbirlerinden farklı kalmışlardır. Mısır hiyeroglif yazıtlarının bilinen en eski kanıtı hanedan öncesi dönemde, yaklaşık MÖ 3200'e tarihlenen Nakada III çömlek kaplarında görülmüştür.[40]

Kral Menes tarafından MÖ 3150 dolaylarında birleşik bir krallık kuruldu ve bu, sonraki üç bin yıl boyunca Mısır'ı yöneten bir dizi hanedanlığın ortaya çıkmasına zemin hazırladı. Mısır kültürü bu uzun dönemde gelişti ve dini, sanatı, dili ve gelenekleri bakımından Mısırlılara özgü olarak kaldı. Birleşik bir Mısır'ın ilk iki yönetici hanedanı, MÖ 2700-2200 dolaylarında birçok piramit inşa edilen Eski Krallık dönemine zemin hazırladı. Bu piramitlerden en önemlisi, Zoser'in Üçüncü Hanedan piramidi ve Dördüncü Hanedan'a ait Gize piramitleridir.

Birinci Ara Dönem, yaklaşık 150 yıl süren bir siyasi çalkantı dönemini başlattı.[41] Bununla birlikte, daha güçlü Nil taşkınları ve hükümetin istikrara kavuşması, Orta Krallık'taki ülkeye refahı geri getirdi. MÖ 2040'ta ise Firavun III. Amenemhat döneminde zirveye ulaşıldı. İkinci Ara Dönem, Mısır topraklarındaki ilk yabancı yöneticili bir hanedan olan Sami Hiksos'un gelişinin habercisiydi. Hiksos istilacıları, MÖ 1650 civarında Aşağı Mısır'ın çoğunu ele geçirdiler ve Avaris'te yeni bir başkent kurdular. İstilacılar Mısır'daki on sekizinci hanedanı kuran ve başkenti Memfis'ten Teb'e taşıyan I. Ahmose liderliğindeki Yukarı Mısır kuvvetleri tarafından kovuldular.

MÖ 1550-1070 dolaylarındaki Yeni Krallık, on sekizinci hanedan dönemi ile başladı ve Mısır'ın, Nübye'deki Tombos'a kadar güneydeki bir imparatorluğa kadar genişleyen ve doğuda Levant'ın bazı kısımlarını da kapsayan uluslararası bir güç olarak yükselişini temsil ediyordu. Bu dönem Hatşepsut, III. Thutmose, Akhenaton ve eşi Nefertiti, Tutankhamun ve II. Ramses gibi en tanınmış Firavunlardan bazılarını içermektedir. Monoteizm, bu dönemde "Atenizm" olarak ortaya çıktı. Ülke daha sonra Libyalılar, Nübyeliler ve Asurlular tarafından işgal edildi ve bu işgal, yerli Mısırlılar'ın işgalcileri kovmasına ve ülkelerinin kontrolünü yeniden ele geçirmesine kadar devam etti.[42]

MÖ 525'te II. Kambises liderliğindeki Ahameniş İmparatorluğu Mısır akınlarına başladı ve sonunda Pelusium savaşında firavun III. Psamtik esir düştü. II. Kambises daha sonra resmî olarak firavun unvanını aldı ancak Mısır'ı günümüzde İran sınırları içinde yer alan Susa'daki evinden yöneterek Mısır'ı bir satraplığın kontrolü altına bıraktı. Ahamenişlere karşı geçici olarak başarılı olan birkaç isyan MÖ 5. yüzyıla damgasını vursa da Mısır hiçbir zaman Ahamenişleri kalıcı olarak devirmeyi başaramadı.[43]

Otuzuncu hanedan, Firavunlar döneminde hüküm süren son yerli hanedan olma özelliğini taşımaktadır. Mısır, son yerli Firavun Kral II. Nektanebo'nun savaşta yenilmesinden sonra MÖ 343'te yeniden Ahamenişlerin eline geçti. Mısır'daki bu hanedanlık uzun ömürlü değildi çünkü Ahamenişler birkaç on yıl sonra Büyük İskender tarafından devrildi. İskender'in Makedon generali I. Ptolemaios burada Ptolemaios Hanedanı'nı kurdu.[44]

Ptolemaios ve Roma Mısırı[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Ptolemaios Krallığı doğuda Güney Suriye'den batıda Kirene'ye ve güneyde Nübye sınırına kadar uzanan güçlü bir Helenistik devletti. Başkent ve ülke merkezi İskenderiye oldu. Bu süre içinde Mısır'da ekonomik ve mimari gelişmeler yaşandı. Bunun yanında Roma-Mısır kültürü kaynaşması da oldu. Yunan mimarisi ve kültürü, Mısır'a ulaştı. Ptolemaioslar Yerli Mısır halkı tarafından benimsenmek amacıyla kendilerini Firavunların vârisleri olarak adlandırdılar. Mısır geleneklerini benimsediler, kendilerini Mısır tarzı ve kıyafetiyle halka açık anıtlarda resmettirdiler ve Mısırlıların dinî yaşamına katıldılar.[45][46]

Ptolemaios soyunun son hükümdarı, Octavianus'un İskenderiye'yi ele geçirmesi ve paralı askerlerinin kaçması ile birlikte sevgilisi Marcus Antonius'un ölümünün ardından intihar eden VII. Kleopatra'ydı. Ptolemaioslar sık sık yerli Mısırlıların isyanlarıyla karşı karşıya kaldılar ve krallığın gerilemesine ve Roma tarafından ilhak edilmesine yol açan dış ve iç savaşlara karıştılar.

Hristiyanlık, 1. yüzyılda Evanjelist Markos ile birlikte Mısır'a geldi.[47] Diocletianus'un hükümdarlığı (MS 284-305), Mısır'da çok sayıda Mısırlı Hristiyan'ın zulme uğradığı Roma döneminden Bizans dönemine geçişi işaret ediyordu. O zamana kadar Yeni Ahit Mısır diline tercüme edilmişti. MS 451'deki Kalkedon Konsili'nden sonra, ayrı bir Mısır Kıptî Kilisesi kuruldu.[48]

Orta Çağ (7. yüzyıl - 1517)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Bizanslılar, 602-628 Bizans-Sasani Savaşı'nın ortasında, 7. yüzyılın başlarında kısa bir Sasani istilasının ardından ülkenin kontrolünü yeniden ele geçirmeyi başardılar ve bu sırada on yıl boyunca Sasani Mısır olarak bilinen kısa ömürlü yeni bir eyalet kurdular. Bu eyalet Mısır'ın Araplar tarafından fethine kadar sürdü. Araplar Mısır'da Bizans ordularını mağlup edince İslam Mısır'da yayılmaya başladı. Bu dönemde bir süre Mısırlılar yeni inançlarını yerli inanç ve uygulamalarla harmanlamaya başladılar ve bu da bugüne kadar gelişen çeşitli Sufi tarikatlarının oluşmasına yol açtı. Bu dönemde bir süre Mısırlılar yeni inançlarını yerli inanç ve uygulamalarla harmanlamaya başladılar ve bu da bugüne kadar gelişen çeşitli Sûfî tarikatlarının oluşmasına yol açtı.[47]

Mısır üzerine 639'da yürüyen Amr bin Âs komutasındaki Arap kuvvetleri delta bölgesinin doğusundaki direnişi kırarak 641'de Doğu Roma İmparatorluğu'nu (Bizans) barış yapmaya zorladı. Bizans kuvvetlerinin geri çekilmesinden sonra 8 Kasım 641'de İskenderiye de Arapların eline geçti. İskenderiye 645'te Bizans İmparatorluğu kuvvetleri tarafından geri alındı ancak 646'da Amr tarafından tekrar Arapların eline geçti. 654 yılında II. Konstans'ın gönderdiği istila filosu geri püskürtüldü.

İlk Arap yerleşimi olarak Nil'in doğu kıyısında kurulan el-Fustat uzun süre tek Müslüman merkezi olarak kaldı. Şehir daha sonra Haçlı Seferleri sırasında yakıldı. Kahire daha sonra 986 yılında Arap halifeliğinin Bağdat'tan sonra ikinci en büyük ve en zengin şehri olması amacıyla inşa edildi.

Abbâsîler dönemi[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Abbâsîler döneminde yeni vergiler getirildi ve Kıptîler, Abbâsî yönetiminin dördüncü yılında isyan çıkardı. 9. yüzyılın başlarında Mısır'ı bir vali aracılığıyla yönetme uygulaması, Bağdat'ta ikamet etmeye karar veren ve kendisi adına yönetmesi için Mısır'a bir vekil gönderen Abdullah ibn Tahir döneminde yeniden başladı. 828'de Mısır'da başka bir isyan daha patlak verdi ve 831'de Kıptîler hükûmete karşı yerli Müslümanlarla birlik kurdu.

Bağdat'taki halifelik merkezinden Mısır'ı yönetme güçlüğü sonraki yıllarda sık sık vali değişikliğine başvurmaya yol açtı. IX. Yüzyılın ortalarından itibaren Bağdat tarafından gönderilen valilerin yerini valiliklerini Bağdat'a tasdik ettiren Türk komutanlar aldı. Itah (Aytah) Türkî (847-848), Hakan oğlu el-Fethi't-Türkî (856-861), Dinar oğlu Yezidi't-Türkî (856-867), Müzahimü't-Türkî (867-868), Ahmedü' Türkî (868) ve Uluğ Tarhan oğlu Uzcur Türkî (868) Sudan ile birlikte Mısır'a valilik yapan ilk altı Türk komutandır. 15 Eylül 868'de bir başka Türk vali Ahmed bin Tolun Mısır'a gelerek Mısır'da ilk Türk hanedanını kurmuştur.

Fâtımîler, Eyyûbîler ve Memlûkler[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Sonraki altı yüzyıl boyunca Mısır'ın kontrolü Müslüman yöneticilerde kaldı. Kahire, Fâtımîler'in merkeziydi. Eyyûbîler hanedanının sona ermesiyle birlikte, Türk-Çerkes askerî kastı olan Memlûkler 1250 yılı civarında kontrolü ele geçirdi. 13. yüzyılın sonlarında Mısır, Kızıldeniz, Hindistan, Malaya ve Doğu Hint Adaları'nı birbirine bağladı.[49] 14. yüzyılın ortalarında Kara Ölüm, ülke nüfusunun yaklaşık %40'ının ölümüne sebep oldu.[50]

Erken modern dönem: Osmanlı dönemi (1517 - 1867)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

1517 yılında Yavuz Sultan Selim'in Ridaniye Muharebesi'yle Memlûk Sultanlığı'nı yıkarak Mısır'ı Osmanlı topraklarına katması sonucunda Mısır Eyaleti kuruldu, halifelik de Türklere geçti.

Savunma amaçlı militarizasyon sivil toplum yapısına ve ekonomik kurumlara zarar verdi.[49] Ekonomik sistemin zayıflaması vebanın etkileriyle birleşerek Mısır'ı yabancı işgaline karşı savunmasız bıraktı. Portekizli tüccarlar ticareti devraldı.[49] 1687 ile 1731 yılları arasında Mısır'da altı adet kıtlık yaşandı.[52] 1784'teki kıtlık, nüfusunun yaklaşık altıda birine mal oldu.[53]

Mısır, ülkeyi yüzyıllardır yöneten Memlûklerin devam eden gücü ve etkisi nedeniyle, Osmanlı padişahları için çoğu zaman kontrol edilmesi zor bir eyalet olmuştur.

Mısır, 1798'de Napolyon Bonapart'ın Fransız kuvvetleri tarafından işgal edilene kadar Memlûk yönetimi altında yarı özerk olarak kaldı. Fransızların İngilizlere yenilmesinin ardından Osmanlı Türkleri, yüzyıllarca Mısır'ı yöneten Mısırlı Memlûkler ve Osmanlı'nın hizmetinde olan Arnavut paralı askerleri arasında üçlü bir iktidar mücadelesi yaşandı.

Kavalalılar Hanedanı dönemi[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Fransızların sınır dışı edilmesinin ardından, 1805 yılında Mısır'daki Osmanlı ordusunun Arnavut kökenli askerî komutanı Mehmed Ali Paşa tarafından iktidara el konuldu. Muhammed Ali, Memlûkleri katletti ve 1952 devrimine kadar Mısır'ı yönetecek bir hanedan kurdu.

Mehmed Ali Paşa, Kuzey Sudan'ı (1820-1824), Suriye'yi (1833) ve Arabistan ile Anadolu'nun bazı kısımlarını ilhak etti. 1841'de Avrupalı güçler, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nu devirme ihtimalinden çekinerek Kavalalı'yı fethettiği yerlerin çoğunu Osmanlılara iade etmeye zorladı. Askeriyeye olan tutkusu onu ülkeyi modernleştirmeye zorladı. Sanayiler inşa etti, sulama ve ulaşım için bir kanal sistemi kurdu ve kamu hizmetinde reform yaptı.[55]

Mısır'ı Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nda güçlü bir konuma yükseltmek için, 20. yüzyılda yürütülen komünizm harici Sovyet stratejileriyle çeşitli benzerlikler gösterecek şekilde, halkın yaklaşık yüzde 4'ünün orduya hizmet ettiği bir askerî devlet inşa etti.[56]

Mehmed Ali Paşa, orduyu angarya geleneği altında toplanan bir ordudan büyük, modern bir orduya dönüştürdü. 19. yüzyıl Mısır'ında erkek köylülerin zorunlu askerliğini başlattı ve büyük ordusunu desteklemek için yeni bir yaklaşım benimseyerek onu sayı ve beceri açısından güçlendirdi. Yeni askerlerin eğitim ve öğretimi zorunlu hale getirildi. Erkekler, olası aksi bir durumun önüne geçebilinmesi amacıyla kışlalarda tutuldu. Erkeklerde askerî yaşam tarzına yönelik karşıtlık zamanla azaldı ve milliyetçiliğe dayalı yeni bir ideoloji benimsendi. Mehmed Ali Paşa, bu yeni doğan askerî birliğin yardımıyla Mısır'daki hakimiyetini güçlendirdi.[57]

Mehmed Ali Paşa'nın hükümdarlığı sırasında izlediği bu politika, ileri eğitime yatırımın yalnızca askerî ve sanayi alanında gerçekleşmesi nedeniyle Mısır'daki sayısal becerinin diğer Kuzey Afrika ve Orta Doğu ülkeleriyle karşılaştırıldığında neden dikkate değer derecede küçük bir oranda arttığını kısmen açıklamaktadır.[58]

Muhammed Ali'nin yerine kısa süreliğine oğlu İbrahim (Eylül 1848'de), ardından torunu I. Abbas (Kasım 1848'de), ardından Said (1854'te) ve Mısır'da bilimi ve tarımı teşvik eden ve köleliği yasaklayan İsmail (1863'te) geçti.[56]

Mısır Hidivliği (1867-1914)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Mehmed Ali hanedanı yönetimindeki Mısır, bir Osmanlı vilayeti olarak kaldı. 1867'de özerk bir vasal devlet veya Hidivlik statüsü verildi. 1867'de özerk bir vasal devlet (Hidivlik) statüsü verildi.

Fransızlarla ortaklaşa inşa edilen Süveyş Kanalı 1869'da tamamlandı. İnşaatı Avrupalı bankalar tarafından finanse edildi. Himaye ve yolsuzluğa da büyük meblağlar gitmiştir. Yeni vergiler halkın hoşnutsuzluğuna neden oldu. 1875'te İsmail Paşa, Mısır'ın kanaldaki tüm hisselerini İngiliz hükûmetine satarak iflastan kurtuldu. Üç yıl içinde bu, Mısır kabinesinde yer alan ve "tahvil sahiplerinin mali gücünün arkalarında olmasıyla hükümetteki gerçek güç olan" İngiliz ve Fransız kontrolörlerin göreve getirilmesine yol açtı.[59]

Salgın hastalıklar (1880'lerdeki sığır hastalığı), su baskınları ve savaşlar gibi diğer koşullar ekonomik gerilemeyi tetikledi ve Mısır'ın dış borca bağımlılığını daha da artırdı.[60]

Hidiv'den ve Avrupa'nın müdahalesinden duyulan memnuniyetsizlik, 1879'da ilk milliyetçi grupların oluşmasına yol açtı. Ahmed Urabi öne çıkan isimlerden biri idi. Artan gerginlikler ve milliyetçi isyanların ardından Birleşik Krallık, 1882'de Mısır'ı işgal etti. Tell El Kebir Muharebesi'nde Mısır ordusunu ezdi ve ülkeyi askerî olarak fiilen işgal etti.[61] Bunu takiben Hidivlik, sözde Osmanlı egemenliği altında fiili bir İngiliz himayesi haline geldi.[62]

1899'da İngiliz-Mısır Kat Mülkiyeti Anlaşması imzalandı. Anlaşma, Sudan'ın Mısır Hidivliği ve Birleşik Krallık tarafından ortaklaşa yönetileceğini belirtiyordu. Ancak Sudan'ın fiili kontrolü yalnızca İngilizlerin elindeydi.

1906'da Denişvay Olayı birçok tarafsız Mısırlının milliyetçi harekete katılmasına neden oldu.

Mısır Sultanlığı (1914-1922)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

1914'te Osmanlı İmparatorluğu, merkezi imparatorluklarla ittifak halinde Birinci Dünya Savaşı'na resmen girdi. Önceki yıllarda İngilizlere giderek daha fazla düşmanlık geliştiren Hidiv II. Abbas savaşta anavatana destek olmaya karar verdi. Bu kararın ardından İngilizler zorla iktidarına son verdi ve yerine kardeşi Hüseyin Kâmil'i getirdi.[63][64]

Hüseyin Kâmil, Mısır Sultanı unvanını alarak Mısır'ın Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'ndan bağımsızlığını ilan etti. Bağımsızlığın hemen ardından Mısır, Birleşik Krallık'ın himayesi altına alındı.

Birinci Dünya Savaşı'ndan sonra Sad Zağlûl ve Vefd Partisi, Mısır milliyetçi hareketini yerel Yasama Meclisi'nde çoğunluğa kavuşturdu. İngilizler 8 Mart 1919'da Zağlûl ve arkadaşlarını Malta'ya sürgün ettiğinde ülke ilk modern devrimini yaşadı. İsyan, Birleşik Krallık hükûmetinin 22 Şubat 1922'de Mısır'ın bağımsızlığını tek taraflı olarak ilan etmesine yol açtı.[65]

Mısır Krallığı (1922-1953)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Birleşik Krallık'tan bağımsızlığını kazandıktan sonra Sultan I. Fuad, Mısır Kralı unvanını aldı. Sözde bağımsız olmasına rağmen, krallık fiilen hâlâ İngiliz işgali altındaydı ve Birleşik Krallık'ın hâlâ devlet üzerinde büyük etkisi vardı.

Yeni hükûmet 1923 yılında parlamenter sisteme dayalı bir anayasa hazırlayıp uygulamaya koydu. Milliyetçi Vefd Partisi 1923-1924 seçimlerinde ezici bir çoğunlukla zafer kazandı ve Sad Zağlûl yeni başbakan olarak atandı.

1936'da İngiliz-Mısır Antlaşması imzalandı ve İngiliz birlikleri Süveyş Kanalı hariç Mısır'dan çekildi. Anlaşma, mevcut 1899 İngiliz-Mısır Kat Mülkiyeti Anlaşması hükümlerine göre Sudan'ın Mısır ve İngiltere tarafından ortaklaşa yönetilmesi gerektiğini ancak gerçek gücün İngilizlerin elinde kalması gerektiğini belirten Sudan sorununa çözüm bulmadı.[66]

Britanya, Mısır'ı bölgedeki Müttefik operasyonları için, özellikle de Kuzey Afrika'da İtalya ve Almanya'ya karşı yapılan savaşlar için bir üs olarak kullandı. En büyük öncelikleri Doğu Akdeniz'in kontrolü ve özellikle Süveyş Kanalı'nın ticari gemilere ve Hindistan ve Avustralya ile askerî bağlantılara açık tutulmasıydı. Eylül 1939'da savaş başladığında Mısır sıkıyönetim ilan etti ve Almanya ile diplomatik ilişkilerini kesti. 1940 yılında İtalya ile diplomatik ilişkilerini kesti ancak İtalyan ordusu Mısır'ı işgal ettiğinde bile asla savaş ilan etmedi. Mısır ordusu savaşmadı. Haziran 1940'ta Kral, İngilizlerle arası iyi olmayan Başbakan Ali Mahir'i görevden aldı. Bağımsız Hasan Paşa Sabri'nin başbakanlığında yeni bir koalisyon hükûmeti kuruldu.

Şubat 1942'deki bakanlık krizinin ardından, Büyükelçi Miles Lampson, Faruk'a, Hüseyin Sırrı Paşa hükümetinin yerine bir Vefd veya Vefd koalisyon hükümeti kurması için baskı yaptı. 4 Şubat 1942 gecesi İngiliz birlikleri ve tankları Kahire'deki Abidin Sarayı'nı kuşattı ve Lampson, Faruk'a bir ültimatom sundu. Faruk teslim oldu ve Nehhas kısa süre sonra hükümeti kurdu.

İngiliz ordusunun bölgede bir askerî üssü olmasına rağmen İngiliz birliklerinin çoğu 1947'de Süveyş Kanalı bölgesine çekildi. Ülkedeki milliyetçi, İngiliz karşıtı duygular savaştan sonra büyümeye devam etti. Krallığın Birinci Arap-İsrail Savaşı'ndaki talihsiz performansının ardından monarşi karşıtı duygular daha da arttı. 1950 seçimleri milliyetçi Vefd Partisi'nin ezici bir zaferine tanık oldu ve Kral, Mustafa Nehhas Paşa'yı yeni başbakan olarak atamak zorunda kaldı. 1951'de Mısır, 1936 İngiliz-Mısır Antlaşması'ndan tek taraflı olarak çekildi ve geri kalan tüm İngiliz birliklerinin Süveyş Kanalı'nı terk etmesini emretti.

İngilizlerin Süveyş Kanalı çevresindeki üslerini terk etmeyi reddetmesi üzerine Mısır hükümeti suyu kesti ve Süveyş Kanalı üssüne yiyecek tedarikine izin vermedi, İngiliz mallarına boykot ilan etti, Mısırlı işçilerin üsse girmesini yasakladı ve gerilla saldırılarına destek oldu. 24 Ocak 1952'de Mısır gerillaları Süveyş Kanalı çevresinde İngiliz kuvvetlerine şiddetli bir saldırı düzenlerken Mısır polisinin gerillalara yardım ettiği görüldü. Buna cevaben 25 Ocak'ta General George Erskine, İsmailiye'deki polis karakolunun çevrelenmesi için İngiliz tanklarını ve piyadelerini gönderdi. Polis komutanı, Nehhas'ın sağ kolu olan İçişleri Bakanı Fuad Serageddin'i arayarak teslim mi olması yoksa savaşması mı gerektiğini sordu. Serageddin polise "son adama ve son kurşuna kadar" savaşma emri verdi. Ortaya çıkan çatışmada polis karakolu yerle bir edildi ve 43 Mısırlı polis memuru ile 3 İngiliz askeri öldürüldü. İsmailiye olayı Mısır'ı öfkelendirdi. Ertesi gün, 26 Ocak 1952, İngiliz karşıtı isyan olarak bilinen "Kara Cumartesi" olarak tarihe geçti Kanuni Hidiv İsmail'in Paris tarzında yeniden inşa ettiği Kahire şehir merkezinin büyük bir kısmının yanmasına neden oldu. Faruk, Kara Cumartesi isyanından Vefd'i sorumlu tuttu ve ertesi gün Nehhas'ı başbakanlıktan uzaklaştırdı. Yerine Ali Mahir Paşa getirildi.[67]

22-23 Temmuz 1952'de Muhammed Necib ve Cemal Abdülnasır liderliğindeki Hür Subaylar Hareketi, krala karşı bir darbe (1952 Mısır Devrimi) başlattı. I. Faruk, tahtını o sırada yedi aylık bir bebek olan oğlu II. Fuad'a bıraktı. Kraliyet Ailesi birkaç gün sonra Mısır'ı terk etti ve Prens Muhammed Abdülmünim liderliğindeki Vekillik Konseyi kuruldu. Ancak konsey yalnızca nominal yetkiye sahipti ve gerçek güç aslında Necib ve Abdülnasır liderliğindeki Devrimci Komuta Konseyi'nin elindeydi.

Acil reformlara yönelik popüler beklentiler, 12 Ağustos 1952'de Kafr ed-Davvar'da işçi ayaklanmalarına yol açtı. Sivil yönetimle ilgili kısa bir deneyin ardından Hür Subaylar, monarşiyi ve 1923 anayasasını kaldırdı ve 18 Haziran 1953'te Mısır'da cumhuriyeti ilan etti. Necib cumhurbaşkanı ilan edilirken Abdülnasır yeni başbakan olarak atandı.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Republic of Egypt (1953–1958)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Following the 1952 Revolution by the Free Officers Movement, the rule of Egypt passed to military hands and all political parties were banned. On 18 June 1953, the Egyptian Republic was declared, with General Muhammad Naguib as the first President of the Republic, serving in that capacity for a little under one and a half years.

President Nasser (1956–1970)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Naguib was forced to resign in 1954 by Gamal Abdel Nasser – a Pan-Arabist and the real architect of the 1952 movement – and was later put under house arrest. After Naguib's resignation, the position of President was vacant until the election of Nasser in 1956.[68]

In October 1954, Egypt and the United Kingdom agreed to abolish the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement of 1899 and grant Sudan independence; the agreement came into force on 1 January 1956.

Nasser assumed power as president in June 1956. British forces completed their withdrawal from the occupied Suez Canal Zone on 13 June 1956. He nationalised the Suez Canal on 26 July 1956; his hostile approach towards Israel and economic nationalism prompted the beginning of the Second Arab-Israeli War (Suez Crisis), in which Israel (with support from France and the United Kingdom) occupied the Sinai peninsula and the Canal. The war came to an end because of US and USSR diplomatic intervention and the status quo was restored.

United Arab Republic (1958–1971)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

In 1958, Egypt and Syria formed a sovereign union known as the United Arab Republic. The union was short-lived, ending in 1961 when Syria seceded, thus ending the union. During most of its existence, the United Arab Republic was also in a loose confederation with North Yemen (or the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen), known as the United Arab States.

In the early 1960s, Egypt became fully involved in the North Yemen Civil War. Despite several military moves and peace conferences, the war sank into a stalemate.[69]

In mid May 1967, the Soviet Union issued warnings to Nasser of an impending Israeli attack on Syria. Although the chief of staff Mohamed Fawzi verified them as "baseless",[70][71] Nasser took three successive steps that made the war virtually inevitable: on 14 May he deployed his troops in Sinai near the border with Israel, on 19 May he expelled the UN peacekeepers stationed in the Sinai Peninsula border with Israel, and on 23 May he closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping.[72] On 26 May Nasser declared, "The battle will be a general one and our basic objective will be to destroy Israel".[73]

This prompted the beginning of the Third Arab Israeli War (Six-Day War) in which Israel attacked Egypt, and occupied Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip, which Egypt had occupied since the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. During the 1967 war, an Emergency Law was enacted, and remained in effect until 2012, with the exception of an 18-month break in 1980/81.[74] Under this law, police powers were extended, constitutional rights suspended and censorship legalised.[75]

At the time of the fall of the Egyptian monarchy in the early 1950s, less than half a million Egyptians were considered upper class and rich, four million middle class and 17 million lower class and poor.[76] Fewer than half of all primary-school-age children attended school, most of them being boys. Nasser's policies changed this. Land reform and distribution, the dramatic growth in university education, and government support to national industries greatly improved social mobility and flattened the social curve. From academic year 1953–54 through 1965–66, overall public school enrolments more than doubled. Millions of previously poor Egyptians, through education and jobs in the public sector, joined the middle class. Doctors, engineers, teachers, lawyers, journalists, constituted the bulk of the swelling middle class in Egypt under Nasser.[76] During the 1960s, the Egyptian economy went from sluggish to the verge of collapse, the society became less free, and Nasser's appeal waned considerably.[77]

Arab Republic of Egypt (1971–present)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

President Sadat (1970–1981)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

In 1970, President Nasser died and was succeeded by Anwar Sadat. Sadat switched Egypt's Cold War allegiance from the Soviet Union to the United States, expelling Soviet advisors in 1972. He launched the Infitah economic reform policy, while clamping down on religious and secular opposition. In 1973, Egypt, along with Syria, launched the Fourth Arab-Israeli War (Yom Kippur War), a surprise attack to regain part of the Sinai territory Israel had captured 6 years earlier.

In 1975, Sadat shifted Nasser's economic policies and sought to use his popularity to reduce government regulations and encourage foreign investment through his programme of Infitah. Through this policy, incentives such as reduced taxes and import tariffs attracted some investors, but investments were mainly directed at low risk and profitable ventures like tourism and construction, abandoning Egypt's infant industries.[78] Because of the elimination of subsidies on basic foodstuffs, it led to the 1977 Egyptian Bread Riots.

Sadat made a historic visit to Israel in 1977, which led to the 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty in exchange for Israeli withdrawal from Sinai. In return, Egypt recognised Israel as a legitimate sovereign state. Sadat's initiative sparked enormous controversy in the Arab world and led to Egypt's expulsion from the Arab League, but it was supported by most Egyptians.[79] Sadat was assassinated by an Islamic extremist in October 1981.

President Mubarak (1981–2011)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Hosni Mubarak came to power after the assassination of Sadat in a referendum in which he was the only candidate.[80] Hosni Mubarak reaffirmed Egypt's relationship with Israel yet eased the tensions with Egypt's Arab neighbours. Domestically, Mubarak faced serious problems. Mass poverty and unemployment led rural families to stream into cities like Cairo where they ended up in crowded slums, barely managing to survive.

On 25 February 1986, the Security Police started rioting, protesting against reports that their term of duty was to be extended from 3 to 4 years. Hotels, nightclubs, restaurants and casinos were attacked in Cairo and there were riots in other cities. A day time curfew was imposed. It took the army 3 days to restore order. 107 people were killed.[81]

In the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, terrorist attacks in Egypt became numerous and severe, and began to target Christian Copts, foreign tourists and government officials.[82] In the 1990s an Islamist group, Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, engaged in an extended campaign of violence, from the murders and attempted murders of prominent writers and intellectuals, to the repeated targeting of tourists and foreigners. Serious damage was done to the largest sector of Egypt's economy—tourism[83]—and in turn to the government, but it also devastated the livelihoods of many of the people on whom the group depended for support.[84]

During Mubarak's reign, the political scene was dominated by the National Democratic Party, which was created by Sadat in 1978. It passed the 1993 Syndicates Law, 1995 Press Law, and 1999 Nongovernmental Associations Law which hampered freedoms of association and expression by imposing new regulations and draconian penalties on violations.[85] As a result, by the late 1990s parliamentary politics had become virtually irrelevant and alternative avenues for political expression were curtailed as well.[86]

On 17 November 1997, 62 people, mostly tourists, were massacred near Luxor.

In late February 2005, Mubarak announced a reform of the presidential election law, paving the way for multi-candidate polls for the first time since the 1952 movement.[87] However, the new law placed restrictions on the candidates, and led to Mubarak's easy re-election victory.[88] Voter turnout was less than 25%.[89] Election observers also alleged government interference in the election process.[90] After the election, Mubarak imprisoned Ayman Nour, the runner-up.[91]

Human Rights Watch's 2006 report on Egypt detailed serious human rights violations, including routine torture, arbitrary detentions and trials before military and state security courts.[92] In 2007, Amnesty International released a report alleging that Egypt had become an international centre for torture, where other nations send suspects for interrogation, often as part of the War on Terror.[93] Egypt's foreign ministry quickly issued a rebuttal to this report.[94]

Constitutional changes voted on 19 March 2007 prohibited parties from using religion as a basis for political activity, allowed the drafting of a new anti-terrorism law, authorised broad police powers of arrest and surveillance, and gave the president power to dissolve parliament and end judicial election monitoring.[95] In 2009, Dr. Ali El Deen Hilal Dessouki, Media Secretary of the National Democratic Party (NDP), described Egypt as a "pharaonic" political system, and democracy as a "long-term goal". Dessouki also stated that "the real center of power in Egypt is the military".[kaynak belirtilmeli]

Revolution (2011)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Bottom: protests in Tahrir Square against President Morsi on 27 November 2012.

On 25 January 2011, widespread protests began against Mubarak's government. On 11 February 2011, Mubarak resigned and fled Cairo. Jubilant celebrations broke out in Cairo's Tahrir Square at the news.[96] The Egyptian military then assumed the power to govern.[97][98] Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, chairman of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, became the de facto interim head of state.[99][100] On 13 February 2011, the military dissolved the parliament and suspended the constitution.[101]

A constitutional referendum was held on 19 March 2011.[102] On 28 November 2011, Egypt held its first parliamentary election since the previous regime had been in power. Turnout was high and there were no reports of major irregularities or violence.[103]

President Morsi (2012–2013)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Mohamed Morsi was elected president on 24 June 2012.[104] On 30 June 2012, Mohamed Morsi was sworn in as Egypt's president.[105] On 2 August 2012, Egypt's Prime Minister Hisham Qandil announced his 35-member cabinet comprising 28 newcomers, including four from the Muslim Brotherhood.[106]

Liberal and secular groups walked out of the constituent assembly because they believed that it would impose strict Islamic practices, while Muslim Brotherhood backers threw their support behind Morsi.[107] On 22 November 2012, President Morsi issued a temporary declaration immunising his decrees from challenge and seeking to protect the work of the constituent assembly.[108]

The move led to massive protests and violent action throughout Egypt.[109] On 5 December 2012, tens of thousands of supporters and opponents of President Morsi clashed, in what was described as the largest violent battle between Islamists and their foes since the country's revolution.[110] Mohamed Morsi offered a "national dialogue" with opposition leaders but refused to cancel the December 2012 constitutional referendum.[111]

Political crisis (2013)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

On 3 July 2013, after a wave of public discontent with autocratic excesses of Morsi's Muslim Brotherhood government,[112] the military removed Morsi from office, dissolved the Shura Council and installed a temporary interim government.[113]

On 4 July 2013, 68-year-old Chief Justice of the Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt Adly Mansour was sworn in as acting president over the new government following the removal of Morsi.[114] The new Egyptian authorities cracked down on the Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters, jailing thousands and forcefully dispersing pro-Morsi and pro-Brotherhood protests.[115][116] Many of the Muslim Brotherhood leaders and activists have either been sentenced to death or life imprisonment in a series of mass trials.[117][118][119]

On 18 January 2014, the interim government instituted a new constitution following a referendum approved by an overwhelming majority of voters (98.1%). 38.6% of registered voters participated in the referendum[120] a higher number than the 33% who voted in a referendum during Morsi's tenure.[121]

President el-Sisi (2014–present)[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

On 26 March 2014, Field Marshal Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Egyptian Defence Minister and Commander-in-Chief Egyptian Armed Forces, retired from the military, announcing he would stand as a candidate in the 2014 presidential election.[122] The poll, held between 26 and 28 May 2014, resulted in a landslide victory for el-Sisi.[123] Sisi was sworn into office as President of Egypt on 8 June 2014.[124] The Muslim Brotherhood and some liberal and secular activist groups boycotted the vote.[125] Even though the interim authorities extended voting to a third day, the 46% turnout was lower than the 52% turnout in the 2012 election.[126]

A new parliamentary election was held in December 2015, resulting in a landslide victory for pro-Sisi parties, which secured a strong majority in the newly formed House of Representatives.[127]

In 2016, Egypt entered in a diplomatic crisis with Italy following the murder of researcher Giulio Regeni: in April 2016, Prime Minister Matteo Renzi recalled the Italian ambassador from Cairo because of lack of co-operation from the Egyptian Government in the investigation.[128] The ambassador was sent back to Egypt in 2017 by the new Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni.[129]

El-Sisi was re-elected in 2018, facing no serious opposition.[130] In 2019, a series of constitutional amendments were approved by the parliament, further increasing the President's and the military's power, increasing presidential terms from 4 years to 6 years, and allowing incumbent president El-Sisi to run for an additional third term.[131] The proposals were approved in a referendum.[132]

The dispute between Egypt and Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam escalated in 2020.[133][134] Egypt sees the dam as an existential threat,[135] fearing that the dam will reduce the amount of water it receives from the Nile.[136]

In December 2020, final results of the parliamentary election confirmed a clear majority of the seats for Egypt's Mostaqbal Watn (Nation's Future) Party, which strongly supports president el-Sisi. The party even increased its majority, partly because of new electoral rules.[137]

In December 2023, el-Sisi won the 2023 presidential election with 89.6% of the vote, and was re-elected to an additional third term that lasts until 2030. The official turnout was 66.8%, the highest of any Egyptian presidential election since 2012.[138]

Geography[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Egypt's geography is unique and complex, marked by a variety of landforms. The nation spans latitudes 22° to 32°N and longitudes 25° to 35°E, encompassing 1,001,450 square kilometers, making it the world's 30th-largest country. It is distinguished primarily by its expansive deserts, covering about 96% of the land area. This arid landscape offers a harsh environment, with prolific sand dunes that can reach over 30 meters in height. Within the vast desert expanses are a few scattered oases such as Bahariya, Dakhla, Farafra, Kharga, and Siwa.

The population of Egypt is heavily concentrated along the Nile Valley and Delta due to the extreme aridity of its climate. Around 99% of the people inhabit approximately 5.5% of the total land area, with 98% living on just 3% of the territory. The life-giving Nile River not only fosters this dense human habitation but also creates a striking contrast in the landscape as its lush riverbanks carve a path through the desert. In ancient times and even today, the Nile's crucial role in supporting life makes it an object of reverence.

Aside from the Nile Valley, Egypt features the Sinai Peninsula, a land bridge connecting Africa to Asia bordered by Libya to the west; Sudan to the south; and the Gaza Strip and Israel to the east. Sinai hosts Mount Catherine at 2,642 meters above sea level—Egypt's highest peak—and boasts the Red Sea Riviera on its east side with abundant coral reefs and marine life.

Egypt is also home to significant water bodies, including two critical seas—Mediterranean and Red—that provide food resources and economic opportunities through trade routes. The Suez Canal is an essential waterway that pierces through Egypt's western terrain connecting these two seas while facilitating international maritime trade between Europe and Asia.

Major urban centers reflect cultural and historical richness: Cairo as the modern capital; Alexandria as the second-largest city; Luxor and Giza with their archaeological significance; and newer hubs like Sharm El Sheikh on the scenic coastlines. Protectorates such as Ras Mohamed National Park preserve ecological biodiversity in addition to cultural landmarks.

The strategic importance of geographical features like the Sinai Peninsula is underscored by its linkage between continents via Isthmus of Suez. Here lies a navigable waterway—the Suez Canal—trekking between Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean through Red Sea, symbolizing Egypt's economic vitality.

On March 13th, 2015 plans were unveiled for a proposed new capital aiming to further shape Egypt's urban landscape while acknowledging existing towns such as El Mahalla El Kubra, Aswan, Hurghada among others in this transcontinental nation's diverse topography.

-

Egypt lies primarily between latitudes 22° and 32°N, and longitudes 25° and 35°E. At 1.001.450 kilometrekare (386.660 sq mi), it is the world's 30th-largest country.[139] Due to the extreme aridity of Egypt's climate, population centres are concentrated along the narrow Nile Valley and Delta, meaning that about 99% of the population uses about 5.5% of the total land area.[140] 98% of Egyptians live on 3% of the territory.[141]

Egypt is bordered by Libya to the west, the Sudan to the south, and the Gaza Strip and Israel to the east. A transcontinental nation, it possesses a land bridge (the Isthmus of Suez) between Africa and Asia, traversed by a navigable waterway (the Suez Canal) that connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Indian Ocean by way of the Red Sea.

Apart from the Nile Valley, the majority of Egypt's landscape is desert, with a few oases scattered about. Winds create prolific sand dunes that peak at more than 30 metre (100 ft) high. Egypt includes parts of the Sahara desert and of the Libyan Desert.

Sinai peninsula hosts the highest mountain in Egypt, Mount Catherine at 2,642 metres. The Red Sea Riviera, on the east of the peninsula, is renowned for its wealth of coral reefs and marine life.

Towns and cities include Alexandria, the second largest city; Aswan; Asyut; Cairo, the modern Egyptian capital and largest city; El Mahalla El Kubra; Giza, the site of the Pyramid of Khufu; Hurghada; Luxor; Kom Ombo; Port Safaga; Port Said; Sharm El Sheikh; Suez, where the south end of the Suez Canal is located; Zagazig; and Minya. Oases include Bahariya, Dakhla, Farafra, Kharga and Siwa. Protectorates include Ras Mohamed National Park, Zaranik Protectorate and Siwa.

On 13 March 2015, plans for a proposed new capital of Egypt were announced.[142]

Climate[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Most of Egypt's rain falls in the winter months.[143] South of Cairo, rainfall averages only around 2 ila 5 mm (0,1 ila 0,2 in) per year and at intervals of many years. On a very thin strip of the northern coast the rainfall can be as high as 410 mm (16,1 in),[144] mostly between October and March. Snow falls on Sinai's mountains and some of the north coastal cities such as Damietta, Baltim and Sidi Barrani, and rarely in Alexandria. A very small amount of snow fell on Cairo on 13 December 2013, the first time in many decades.[145] Frost is also known in mid-Sinai and mid-Egypt.

Egypt has an unusually hot, sunny and dry climate. Average high temperatures are high in the north but very to extremely high in the rest of the country during summer. The cooler Mediterranean winds consistently blow over the northern sea coast, which helps to get more moderated temperatures, especially at the height of the summertime. The Khamaseen is a hot, dry wind that originates from the vast deserts in the south and blows in the spring or in the early summer. It brings scorching sand and dust particles, and usually brings daytime temperatures over 40 °C (104 °F) and sometimes over 50 °C (122 °F) in the interior, while the relative humidity can drop to 5% or even less.

Prior to the construction of the Aswan Dam, the Nile flooded annually, replenishing Egypt's soil. This gave Egypt a consistent harvest throughout the years.

The potential rise in sea levels due to global warming could threaten Egypt's densely populated coastal strip and have grave consequences for the country's economy, agriculture and industry. Combined with growing demographic pressures, a significant rise in sea levels could turn millions of Egyptians into environmental refugees by the end of the 21st century, according to some climate experts.[146][147]

Biodiversity[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Egypt signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 9 June 1992, and became a party to the convention on 2 June 1994.[148] It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, which was received by the convention on 31 July 1998.[149] Where many CBD National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plans neglect biological kingdoms apart from animals and plants,[150]

The plan stated that the following numbers of species of different groups had been recorded from Egypt: algae (1483 species), animals (about 15,000 species of which more than 10,000 were insects), fungi (more than 627 species), monera (319 species), plants (2426 species), protozoans (371 species). For some major groups, for example lichen-forming fungi and nematode worms, the number was not known. Apart from small and well-studied groups like amphibians, birds, fish, mammals and reptiles, the many of those numbers are likely to increase as further species are recorded from Egypt. For the fungi, including lichen-forming species, for example, subsequent work has shown that over 2200 species have been recorded from Egypt, and the final figure of all fungi actually occurring in the country is expected to be much higher.[151] For the grasses, 284 native and naturalised species have been identified and recorded in Egypt.[152]

Government[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

The House of Representatives, whose members are elected to serve five-year terms, specialises in legislation. Elections were held between November 2011 and January 2012, which were later dissolved. The next parliamentary election was announced to be held within 6 months of the constitution's ratification on 18 January 2014, and were held in two phases, from 17 October to 2 December 2015.[153] Originally, the parliament was to be formed before the president was elected, but interim president Adly Mansour pushed the date.[154] The 2014 Egyptian presidential election took place on 26–28 May. Official figures showed a turnout of 25,578,233 or 47.5%, with Abdel Fattah el-Sisi winning with 23.78 million votes, or 96.9% compared to 757,511 (3.1%) for Hamdeen Sabahi.[155]

After a wave of public discontent with the autocratic excesses[kaynak belirtilmeli] of the Muslim Brotherhood government of President Mohamed Morsi,[112] on 3 July 2013 then-General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi announced the removal of Morsi from office and the suspension of the constitution. A 50-member constitution committee was formed for modifying the constitution, which was later published for public voting and was adopted on 18 January 2014.[156]

In 2024, as part of its Freedom in the World report, Freedom House rated political rights in Egypt at 6 (with 40 representing the most free and 0 the least), and civil liberties at 12 (with 60 being the highest score and 0 the lowest, which gave it the freedom rating of "Not Free".[157] According to the 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices Egypt is the eighth least democratic country in Africa.[158] The 2023 edition of The Economist Democracy Index categorises Egypt as an "authoritarian regime", with a score of 2.93.[159]

Egyptian nationalism predates its Arab counterpart by many decades, having roots in the 19th century and becoming the dominant mode of expression of Egyptian anti-colonial activists and intellectuals until the early 20th century.[160] The ideology espoused by Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood is mostly supported by the lower-middle strata of Egyptian society.[161]

Egypt has the oldest continuous parliamentary tradition in the Arab world.[162] The first popular assembly was established in 1866. It was disbanded as a result of the British occupation of 1882, and the British allowed only a consultative body to sit. In 1923, however, after the country's independence was declared, a new constitution provided for a parliamentary monarchy.[162]

Military and foreign relations[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

The military is influential in the political and economic life of Egypt and exempts itself from laws that apply to other sectors. It enjoys considerable power, prestige and independence within the state and has been widely considered part of the Egyptian "deep state".[80][163][164]

Egypt is speculated by Israel to be the second country in the region with a spy satellite, EgyptSat 1[165] in addition to EgyptSat 2 launched on 16 April 2014.[166]

Bottom: President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi, August 2014.

The United States provides Egypt with annual military assistance, which in 2015 amounted to US$1.3 billion.[167] In 1989, Egypt was designated as a major non-NATO ally of the United States.[168] Nevertheless, ties between the two countries have partially soured since the July 2013 overthrow of Islamist president Mohamed Morsi,[169] with the Obama administration denouncing Egypt over its crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood, and cancelling future military exercises involving the two countries.[170] There have been recent attempts, however, to normalise relations between the two, with both governments frequently calling for mutual support in the fight against regional and international terrorism.[171][172][173] However, following the election of Republican Donald Trump as the President of the United States, the two countries were looking to improve the Egyptian-American relations. On 3 April 2017 al-Sisi met with Trump at the White House, marking the first visit of an Egyptian president to Washington in 8 years. Trump praised al-Sisi in what was reported as a public relations victory for the Egyptian president, and signaled it was time for a normalisation of the relations between Egypt and the US.[174]

Relations with Russia have improved significantly following Mohamed Morsi's removal[175] and both countries have worked since then to strengthen military[176] and trade ties[177] among other aspects of bilateral co-operation. Relations with China have also improved considerably. In 2014, Egypt and China established a bilateral "comprehensive strategic partnership".[178]

The permanent headquarters of the Arab League are located in Cairo and the body's secretary general has traditionally been Egyptian. This position is currently held by former foreign minister Ahmed Aboul Gheit. The Arab League briefly moved from Egypt to Tunis in 1978 to protest the Egypt–Israel peace treaty, but it later returned to Cairo in 1989. Gulf monarchies, including the United Arab Emirates[179] and Saudi Arabia,[180] have pledged billions of dollars to help Egypt overcome its economic difficulties since the overthrow of Morsi.[181]

Following the 1973 war and the subsequent peace treaty, Egypt became the first Arab nation to establish diplomatic relations with Israel. Despite that, Israel is still widely considered as a hostile state by the majority of Egyptians.[182] Egypt has played a historical role as a mediator in resolving various disputes in the Middle East, most notably its handling of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the peace process.[183] Egypt's ceasefire and truce brokering efforts in Gaza have hardly been challenged following Israel's evacuation of its settlements from the strip in 2005, despite increasing animosity towards the Hamas government in Gaza following the ouster of Mohamed Morsi,[184] and despite recent attempts by countries like Turkey and Qatar to take over this role.[185]

Ties between Egypt and other non-Arab Middle Eastern nations, including Iran and Turkey, have often been strained. Tensions with Iran are mostly due to Egypt's peace treaty with Israel and Iran's rivalry with traditional Egyptian allies in the Gulf.[186] Turkey's recent support for the now-banned Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and its alleged involvement in Libya also made both countries bitter regional rivals.[187]

Egypt is a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement and the United Nations. It is also a member of the Fransızca: Organisation internationale de la francophonie, since 1983. Former Egyptian Deputy Prime Minister Boutros Boutros-Ghali served as Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1991 to 1996.

In 2008, Egypt was estimated to have two million African refugees, including over 20,000 Sudanese nationals registered with UNHCR as refugees fleeing armed conflict or asylum seekers. Egypt adopted "harsh, sometimes lethal" methods of border control.[188]

Law[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

The legal system is based on Islamic and civil law (particularly Napoleonic codes); and judicial review by a Supreme Court, which accepts compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction only with reservations.[67]

Islamic jurisprudence is the principal source of legislation. Sharia courts and qadis are run and licensed by the Ministry of Justice.[189] The personal status law that regulates matters such as marriage, divorce and child custody is governed by Sharia. In a family court, a woman's testimony is worth half of a man's testimony.[190]

On 26 December 2012, the Muslim Brotherhood attempted to institutionalise a controversial new constitution. It was approved by the public in a referendum held 15–22 December 2012 with 64% support, but with only 33% electorate participation.[191] It replaced the 2011 Provisional Constitution of Egypt, adopted following the revolution.

The Penal code was unique as it contains a "Blasphemy Law."[192] The present court system allows a death penalty including against an absent individual tried in absentia. Several Americans and Canadians were sentenced to death in 2012.[193]

On 18 January 2014, the interim government successfully institutionalised a more secular constitution.[194] The president is elected to a four-year term and may serve 2 terms.[194] The parliament may impeach the president.[194] Under the constitution, there is a guarantee of gender equality and absolute freedom of thought.[194] The military retains the ability to appoint the national Minister of Defence for the next two full presidential terms since the constitution took effect.[194] Under the constitution, political parties may not be based on "religion, race, gender or geography".[194]

Human rights[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

In 2003, the government established the National Council for Human Rights.[195] Shortly after its foundation, the council came under heavy criticism by local activists, who contend it was a propaganda tool for the government to excuse its own violations[196] and to give legitimacy to repressive laws such as the Emergency Law.[197]

The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life ranks Egypt as the fifth worst country in the world for religious freedom.[198][199] The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, a bipartisan independent agency of the US government, has placed Egypt on its watch list of countries that require close monitoring due to the nature and extent of violations of religious freedom engaged in or tolerated by the government.[200] According to a 2010 Pew Global Attitudes survey, 84% of Egyptians polled supported the death penalty for those who leave Islam; 77% supported whippings and cutting off of hands for theft and robbery; and 82% support stoning a person who commits adultery.[201]

Coptic Christians face discrimination at multiple levels of the government, ranging from underrepresentation in government ministries to laws that limit their ability to build or repair churches.[202] Intolerance towards followers of the Baháʼí Faith, and those of the non-orthodox Muslim sects, such as Sufis, Shi'a and Ahmadis, also remains a problem.[92] When the government moved to computerise identification cards, members of religious minorities, such as Baháʼís, could not obtain identification documents.[203] An Egyptian court ruled in early 2008 that members of other faiths may obtain identity cards without listing their faiths, and without becoming officially recognised.[204]

Clashes continued between police and supporters of former President Mohamed Morsi. During violent clashes that ensued as part of the August 2013 sit-in dispersal, 595 protesters were killed[205] with 14 August 2013 becoming the single deadliest day in Egypt's modern history.[206]

Egypt actively practices capital punishment. Egypt's authorities do not release figures on death sentences and executions, despite repeated requests over the years by human rights organisations.[207] The United Nations human rights office[208] and various NGOs[207][209] expressed "deep alarm" after an Egyptian Minya Criminal Court sentenced 529 people to death in a single hearing on 25 March 2014. Sentenced supporters of former President Mohamed Morsi were to be executed for their alleged role in violence following his removal in July 2013. The judgement was condemned as a violation of international law.[210] By May 2014, approximately 16,000 people (and as high as more than 40,000 by one independent count, according to The Economist),[211] mostly Brotherhood members or supporters, have been imprisoned after Morsi's removal[212] after the Muslim Brotherhood was labelled as terrorist organisation by the post-Morsi interim Egyptian government.[213] According to human rights groups there are some 60,000 political prisoners in Egypt.[214][215]

Homosexuality is illegal in Egypt.[217] According to a 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center, 95% of Egyptians believe that homosexuality should not be accepted by society.[218]

In 2017, Cairo was voted the most dangerous megacity for women with more than 10 million inhabitants in a poll by Thomson Reuters Foundation. Sexual harassment was described as occurring on a daily basis.[219]

Freedom of the press[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Reporters Without Borders ranked Egypt in their 2017 World Press Freedom Index at No. 160 out of 180 nations. At least 18 journalists were imprisoned in Egypt, (2015 itibarıyla). A new anti-terror law was enacted in August 2015 that threatens members of the media with fines ranging from about US$25,000 to $60,000 for the distribution of wrong information on acts of terror inside the country "that differ from official declarations of the Egyptian Department of Defense".[220]

Some critics of the government have been arrested for allegedly spreading false information about the COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt.[221][222]

Administrative divisions[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Egypt is divided into 27 governorates. The governorates are further divided into regions. The regions contain towns and villages. Each governorate has a capital, sometimes carrying the same name as the governorate.[223]

Economy[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Egypt's economy depends mainly on agriculture, media, petroleum exports, natural gas, and tourism. There are also more than three million Egyptians working abroad, mainly in Libya, Saudi Arabia, the Persian Gulf and Europe. The completion of the Aswan High Dam in 1970 and the resultant Lake Nasser have altered the time-honoured place of the Nile River in the agriculture and ecology of Egypt. A rapidly growing population, limited arable land, and dependence on the Nile all continue to overtax resources and stress the economy.

In 2022, the Egyptian economy entered an ongoing crisis, the Egyptian pound was one of the worst performing currencies,[224] inflation. reached 32.6% and core inflation reached nearly 40% in March.[225]

The government has invested in communications and physical infrastructure. Egypt has received United States foreign aid since 1979 (an average of $2.2 billion per year) and is the third-largest recipient of such funds from the United States following the Iraq war. Egypt's economy mainly relies on these sources of income: tourism, remittances from Egyptians working abroad and revenues from the Suez Canal.[226]

In recent years, the Egyptian army has expanded its economic influence, dominating sectors such as petrol stations, fish-farming, car manufacturing, media, infrastructure including roads and bridges, and cement production. This hold on various industries has resulted in a suppression of competition, deterring private investment, and leading to adverse effects for ordinary Egyptians, including slower growth, higher prices, and limited opportunities.[227] The military-owned National Service Products Organization (NSPO) continues its expansion by establishing new factories dedicated to producing fertilisers, irrigation equipment, and veterinary vaccines. Businesses operated by the military, such as Wataniya and Safi, which manage patrol stations and bottled water, respectively, remain under government ownership.[228]

Economic conditions have started to improve considerably, after a period of stagnation, due to the adoption of more liberal economic policies by the government as well as increased revenues from tourism and a booming stock market. In its annual report, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has rated Egypt as one of the top countries in the world undertaking economic reforms.[229] Some major economic reforms undertaken by the government since 2003 include a dramatic slashing of customs and tariffs. A new taxation law implemented in 2005 decreased corporate taxes from 40% to the current 20%, resulting in a stated 100% increase in tax revenue by 2006.

Although one of the main obstacles still facing the Egyptian economy is the limited trickle down of wealth to the average population, many Egyptians criticise their government for higher prices of basic goods while their standards of living or purchasing power remains relatively stagnant. Corruption is often cited by Egyptians as the main impediment to further economic growth.[230][231] The government promised major reconstruction of the country's infrastructure, using money paid for the newly acquired third mobile license ($3 billion) by Etisalat in 2006.[232] In the Corruption Perceptions Index 2013, Egypt was ranked 114 out of 177.[233]

An estimated 2.7 million Egyptians abroad contribute actively to the development of their country through remittances (US$7.8 billion in 2009), as well as circulation of human and social capital and investment.[234] Remittances, money earned by Egyptians living abroad and sent home, reached a record US$21 billion in 2012, according to the World Bank.[235]

Egyptian society is moderately unequal in terms of income distribution, with an estimated 35–40% of Egypt's population earning less than the equivalent of $2 a day, while only around 2–3% may be considered wealthy.[236]

Tourism[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Tourism is one of the most important sectors in Egypt's economy. More than 12.8 million tourists visited Egypt in 2008, providing revenues of nearly $11 billion. The tourism sector employs about 12% of Egypt's workforce.[237] Tourism Minister Hisham Zaazou told industry professionals and reporters that tourism generated some $9.4 billion in 2012, a slight increase over the $9 billion seen in 2011.[238]

The Giza Necropolis is one of Egypt's best-known tourist attractions; it is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still in existence.

Egypt's beaches on the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, which extend to over 3,000 kilometre (1,864 mil), are also popular tourist destinations; the Gulf of Aqaba beaches, Safaga, Sharm el-Sheikh, Hurghada, Luxor, Dahab, Ras Sidr and Marsa Alam are popular sites.

Energy[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Egypt has a developed energy market based on coal, oil, natural gas, and hydro power. Substantial coal deposits in the northeast Sinai are mined at the rate of about 600.000 ton (590.000 emperyal ton; 660.000 küçük ton) per year. Oil and gas are produced in the western desert regions, the Gulf of Suez, and the Nile Delta. Egypt has huge reserves of gas, estimated at 2.180 kilometreküp (520 cu mi),[239] and LNG up to 2012 exported to many countries. In 2013, the Egyptian General Petroleum Co (EGPC) said the country will cut exports of natural gas and tell major industries to slow output this summer to avoid an energy crisis and stave off political unrest, Reuters has reported. Egypt is counting on top liquid natural gas (LNG) exporter Qatar to obtain additional gas volumes in summer, while encouraging factories to plan their annual maintenance for those months of peak demand, said EGPC chairman, Tarek El Barkatawy. Egypt produces its own energy, but has been a net oil importer since 2008 and is rapidly becoming a net importer of natural gas.[240]

Egypt produced 691,000 bbl/d of oil and 2,141.05 Tcf of natural gas in 2013, making the country the largest non-OPEC producer of oil and the second-largest dry natural gas producer in Africa. In 2013, Egypt was the largest consumer of oil and natural gas in Africa, as more than 20% of total oil consumption and more than 40% of total dry natural gas consumption in Africa. Also, Egypt possesses the largest oil refinery capacity in Africa 726,000 bbl/d (in 2012).[239]

Egypt is currently building its first nuclear power plant in El Dabaa, in the northern part of the country, with $25 billion in Russian financing.[241]

Transport[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Transport in Egypt is centred around Cairo and largely follows the pattern of settlement along the Nile. The main line of the nation's 40.800-kilometre (25.400 mi) railway network runs from Alexandria to Aswan and is operated by Egyptian National Railways. The vehicle road network has expanded rapidly to over 34.000 km (21.000 mi), consisting of 28 line, 796 stations, 1800 train covering the Nile Valley and Nile Delta, the Mediterranean and Red Sea coasts, the Sinai, and the Western oases.

The Cairo Metro consists of three operational lines with a fourth line expected in the future.

EgyptAir, which is now the country's flag carrier and largest airline, was founded in 1932 by Egyptian industrialist Talaat Harb, today owned by the Egyptian government. The airline is based at Cairo International Airport, its main hub, operating scheduled passenger and freight services to more than 75 destinations in the Middle East, Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The Current EgyptAir fleet includes 80 aeroplanes.

Suez Canal[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

The Suez Canal is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows ship transport between Europe and Asia without navigation around Africa. The northern terminus is Port Said and the southern terminus is Port Tawfiq at the city of Suez. Ismailia lies on its west bank, 3 kilometre (1+7⁄8 mil) from the half-way point.

The canal is 19.330 km (12.011+1⁄8 mi) long, 24 metre (79 fit) deep and 205 m (673 ft) wide (2010 itibarıyla). It consists of the northern access channel of 22 km (14 mi), the canal itself of 16.225 km (10.081+3⁄4 mi) and the southern access channel of 9 km (5+1⁄2 mi). The canal is a single lane with passing places in the Ballah By-Pass and the Great Bitter Lake. It contains no locks; seawater flows freely through the canal.

On 26 August 2014 a proposal was made for opening a New Suez Canal. Work on the New Suez Canal was completed in July 2015.[242][243] The channel was officially inaugurated with a ceremony attended by foreign leaders and featuring military flyovers on 6 August 2015, in accordance with the budgets laid out for the project.[244][245]

Water supply and sanitation[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

The piped water supply in Egypt increased between 1990 and 2010 from 89% to 100% in urban areas and from 39% to 93% in rural areas despite rapid population growth. Over that period, Egypt achieved the elimination of open defecation in rural areas and invested in infrastructure. Access to an improved water source in Egypt is now practically universal with a rate of 99%. About one half of the population is connected to sanitary sewers.[246]

Partly because of low sanitation coverage about 17,000 children die each year because of diarrhoea.[247] Another challenge is low cost recovery due to water tariffs that are among the lowest in the world. This in turn requires government subsidies even for operating costs, a situation that has been aggravated by salary increases without tariff increases after the Arab Spring. Poor operation of facilities, such as water and wastewater treatment plants, as well as limited government accountability and transparency, are also issues.

Due to the absence of appreciable rainfall, Egypt's agriculture depends entirely on irrigation. The main source of irrigation water is the river Nile of which the flow is controlled by the high dam at Aswan. It releases, on average, 55 cubic kilometres (45,000,000 acre·ft) water per year, of which some 46 cubic kilometres (37,000,000 acre·ft) are diverted into the irrigation canals.[248]

In the Nile valley and delta, almost 33,600 square kilometres (13,000 sq mi) of land benefit from these irrigation waters producing on average 1.8 crops per year.[248]

Demographics[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Egypt is the most populated country in the Arab world and the third most populous on the African continent, with about 95 million inhabitants (2017 itibarıyla).[249] Its population grew rapidly from 1970 to 2010 due to medical advances and increases in agricultural productivity[250] enabled by the Green Revolution.[251] Egypt's population was estimated at 3 million when Napoleon invaded the country in 1798.[252]

Egypt's people are highly urbanised, being concentrated along the Nile (notably Cairo and Alexandria), in the Delta and near the Suez Canal. Egyptians are divided demographically into those who live in the major urban centres and the fellahin, or farmers, that reside in rural villages. The total inhabited area constitutes only 77,041 km², putting the physiological density at over 1,200 people per km2, similar to Bangladesh.

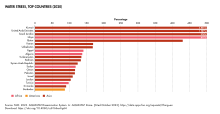

While emigration was restricted under Nasser, thousands of Egyptian professionals were dispatched abroad in the context of the Arab Cold War.[253] Egyptian emigration was liberalised in 1971, under President Sadat, reaching record numbers after the 1973 oil crisis.[254] An estimated 2.7 million Egyptians live abroad. Approximately 70% of Egyptian migrants live in Arab countries (923,600 in Saudi Arabia, 332,600 in Libya, 226,850 in Jordan, 190,550 in Kuwait with the rest elsewhere in the region) and the remaining 30% reside mostly in Europe and North America (318,000 in the United States, 110,000 in Canada and 90,000 in Italy).[234] The process of emigrating to non-Arab states has been ongoing since the 1950s.[255]

Ethnic groups[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Ethnic Egyptians are by far the largest ethnic group in the country, constituting 99.7% of the total population.[67] Ethnic minorities include the Abazas, Turks, Greeks, Bedouin Arab tribes living in the eastern deserts and the Sinai Peninsula, the Berber-speaking Siwis (Amazigh) of the Siwa Oasis, and the Nubian communities clustered along the Nile. There are also tribal Beja communities concentrated in the southeasternmost corner of the country, and a number of Dom clans mostly in the Nile Delta and Faiyum who are progressively becoming assimilated as urbanisation increases.

Some 5 million immigrants live in Egypt, mostly Sudanese, "some of whom have lived in Egypt for generations".[256] Smaller numbers of immigrants come from Iraq, Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan, and Eritrea.[256]

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that the total number of "people of concern" (refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless people) was about 250,000. In 2015, the number of registered Syrian refugees in Egypt was 117,000, a decrease from the previous year.[256] Egyptian government claims that a half-million Syrian refugees live in Egypt are thought to be exaggerated.[256] There are 28,000 registered Sudanese refugees in Egypt.[256]

Jewish communities in Egypt have almost disappeared. Several important Jewish archaeological and historical sites are found in Cairo, Alexandria and other cities.

Languages[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

The official language of the Republic is Literary Arabic.[257] The spoken languages are: Egyptian Arabic (68%), Sa'idi Arabic (29%), Eastern Egyptian Bedawi Arabic (1.6%), Sudanese Arabic (0.6%), Domari (0.3%), Nobiin (0.3%), Beja (0.1%), Siwi and others.[kaynak belirtilmeli] Additionally, Greek, Armenian and Italian, and more recently, African languages like Amharic and Tigrigna are the main languages of immigrants.

The main foreign languages taught in schools, by order of popularity, are English, French, German and Italian.

Historically Egyptian was spoken, the latest stage of which is Coptic Egyptian. Spoken Coptic was mostly extinct by the 17th century but may have survived in isolated pockets in Upper Egypt as late as the 19th century. It remains in use as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.[258][259] It forms a separate branch among the family of Afroasiatic languages.

Religion[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Egypt has the largest Muslim population in the Arab world, and the sixth world's largest Muslim population, and home for (5%) of the world's Muslim population.[260] Egypt also has the largest Christian population in the Middle East and North Africa.[261]

Egypt is a predominantly Sunni Muslim country with Islam as its state religion. The percentage of adherents of various religions is a controversial topic in Egypt. An estimated 85–90% are identified as Muslim, 10–15% as Coptic Christians, and 1% as other Christian denominations, although without a census the numbers cannot be known. Other estimates put the Christian population as high as 15–20%.[c] Non-denominational Muslims form roughly 12% of the population.[268][269]

Egypt was a Christian country before the 7th century, and after Islam arrived, the country was gradually Islamised into a majority-Muslim country.[270][271] It is not known when Muslims reached a majority variously estimated from y. 1000 CE to as late as the 14th century. Egypt emerged as a centre of politics and culture in the Muslim world. Under Anwar Sadat, Islam became the official state religion and Sharia the main source of law.[272] It is estimated that 15 million Egyptians follow Native Sufi orders,[273][274] with the Sufi leadership asserting that the numbers are much greater as many Egyptian Sufis are not officially registered with a Sufi order.[273] At least 305 people were killed during a November 2017 attack on a Sufi mosque in Sinai.[275]

There is also a Shi'a minority. The Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs estimates the Shia population at 1 to 2.2 million[276] and could measure as much as 3 million.[277] The Ahmadiyya population is estimated at less than 50,000,[278] whereas the Salafi (ultra-conservative Sunni) population is estimated at five to six million.[279] Cairo is famous for its numerous mosque minarets and has been dubbed "The City of 1,000 Minarets".[280]

Of the Christian population in Egypt over 90% belong to the native Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, an Oriental Orthodox Christian Church.[281] Other native Egyptian Christians are adherents of the Coptic Catholic Church, the Evangelical Church of Egypt and various other Protestant denominations. Non-native Christian communities are largely found in the urban regions of Cairo and Alexandria, such as the Syro-Lebanese, who belong to Greek Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Maronite Catholic denominations.[282]

Egypt hosts the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. It was founded back in the first century, considered to be the largest church in the country.

Egypt is also the home of Al-Azhar University (founded in 969 CE, began teaching in 975 CE), which is today the world's "most influential voice of establishment Sunni Islam" and is, by some measures, the second-oldest continuously operating university in the world.[283]