Kullanıcı:Brcan/Deneme/Tek başına çeviriler/Çalışma 1

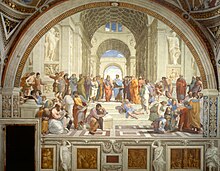

Antik Yunan felsefesi[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Antik Yunan felsefesi, MÖ. 6. yüzyılda başlamış ve Hellenistik çağ ile Roma İmparatorluğu arasında devam etmiştir. Felsefe kelimesi Yunanlar tarafından kullanılmaya başlandı. Önceleri bilimi, matematiği, siyaseti ve etiği de kapsayan bir terimdi. [1] Yunan felsefesi Batı medeniyetinin bir ürünüydü. [2], Roma'da, Rönesans'ta, Aydınlanma çağında ve İslam filozofları tarafından kullanıldı.[3] Yunan felsefesi Antik Yakın Doğu felsefesinden etkilenmiş olabilir. [4]

En önemli filozofların bazıları Sokrates, Aristoteles, Platon ve Pers İmparatorlu'nu fethetmeden önce Yunan felsefesi öğrenmiş olan Büyük İskender şeklinde sıralanabilir.

Birçok filozof matematiğin tüm bilgelikler arasında en önemlisi olduğunu düşünmüştür. Elemanlar adında Geometri üzerine ünlü bir kitabı yazan Öklit matematiğin kurucularından birisidir.

Sokrates öncesi[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Sokrates'in onlara karşı sözleriyle bilinen Protagoras dahil birçok sofist yaşıyordu.

Pisagor teoremi ile bilinen Pisagor bir gizemci ya da akılcı olabilir fakat bu konuda yeterince bilgi bulunmamaktadır. [5]

Klasik Yunan felsefesi[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Sokrates[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Sokrates'in Atina'da MÖ. 5. yüzyılda doğduğu düşünülüyor. Atina öğrenme ve fikir alışverişinde bulunulan bir yerdi. Yine de, felsefe bir suç haline geldi. [6][7] Fakat Sokrates, MÖ. 399 yılında idam edilen tek kișiydi. Platon, Sokrates'in Savunması adında bir kitap yazmıştır. Sokrates siyaset felsefesinin kurucusu sayılır. [8][9][10][11][12][13]

Socrates taught that no one wants what is bad, and so if anyone does something bad, it must be unintentional out of ignorance; he concludes that all virtue is knowledge.[14][15] He often talks about his own ignorance.[16]

Aristotle influenced Plato's dialogues and Plato's student Aristotle. Their ideas influenced the Roman empire, the Islamic Golden Age, and the Renaissance.

Plato[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Plato was from Athenian. He came a generation after Socrates. He wrote thirty-six dialogues and thirteen letters to Socrates, though some may be fake.[17][18]

Plato's dialogues have Socrates. Along with Xenophon, Plato is the primary source of information about Socrates' life. Socrates was known for irony and not often giving own opinions.[19]

Plato wrote the Republic, the Laws, and the Statesman. The Republic says there will not be justice in cities unless they are ruled by philosopher kings; those who enforcing the laws should treat their women, children, and property in common; and the individual should tell noble lies to promote the common good. The Republic says that such a city is likely impossible as it thinks philosophers would refuse to rule and the people would refuse to be ruled by philosophers.[20]

Plato is known for his theory of forms. It says that there are non-physical abstract ideas that have the highest form and most real kind of reality.

Aristotle[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Aristotle moved to Athens in 367 BC and began to study philosophy. He studied at Plato's Academy.[21] He left Athens twenty years later to study botany and zoology. He became a teacher of Alexander the Great and returned to Athens ten years later to create his own school: the Lyceum.[22] At least twenty-nine of his books have survived, known as the corpus Aristotelicum. He wrote about logic, physics, optics, metaphysics, ethics, rhetoric, politics, poetry, botany, and zoology.

Aristotle disagreed with his teacher Plato. He criticizes the governments in Plato's Republic and Laws,[23] and refers to the theory of forms as "empty words and poetic metaphors."[24] He cares more about empirical observation and practical concerns.

Aristotle was not that famous during the Hellenistic period, when Stoic logic was still popular. But later people popularized his work, which influenced Islamic, Jewish, and Christian philosophy.[25] Avicenna referred to him simply as "the Master"; Maimonides, Alfarabi, Averroes, and Aquinas referred to him as "the Philosopher."

Islam[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

During the Middle Ages, Greek ideas were largely forgotten in Western Europe due to the Migration Period, which caused a decline in literacy. In the Byzantine Empire Greek ideas were kept and studied.

After the expansion of Islam, the Abbasid caliphs started translating Greek philosophy. Islamic philosophers such as Al-Kindi (Alkindus), Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn Sina (Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Averroes) reinterpreted these works. During the High Middle Ages Greek philosophy re-entered the West through translations from Arabic to Latin and also from the Byzantine Empire.[26]

The re-introduction of these philosophies, plus new Arabic commentaries, had great influence on Medieval philosophers such as Thomas Aquinas.

Still Arab translators threw away books that disagreed with Islam. For example, Al-Mansur Ibn and Abi Aamir burned the Al-hakam II library in Córdoba in 976.[27][28]

Ayrıca bakınız[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

Kaynakça[değiştir | kaynağı değiştir]

- ^ "Ancient Greek philosophy, Herodotus, famous ancient Greek philosophers. Ancient Greek philosophy at Hellenism.Net". www.hellenism.net. Erişim tarihi: 2019-01-28.

- ^ Alfred North Whitehead (1929), Process and Reality, Part II, Chap. I, Sect. I.

- ^ Kevin Scharp (Department of Philosophy, Ohio State University) – Diagrams 2014-10-31 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi..

- ^ Griffin, Jasper; Boardman, John; Murray, Oswyn (2001). The Oxford history of Greece and the Hellenistic world. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. s. 140. ISBN 978-0-19-280137-1.

- ^ Burnet, Greek Philosophy, 37–38.

- ^ Debra Nails, The People of Plato (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2002), 24.

- ^ Nails, People of Plato, 256.

- ^ Marcus Tullius Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, V 10–11 (or V IV).

- ^ Leo Strauss, Natural Right and History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), 120.

- ^ Seth Benardete, The Argument of the Action (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 277–96.

- ^ Laurence Lampert, How Philosophy Became Socratic (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010).

- ^ Cf. Plato, Republic 336c & 337a, Theaetetus 150c, Apology of Socrates 23a; Xenophon, Memorabilia 4.4.9; Aristotle, Sophistical Refutations 183b7.

- ^ W.K.C. Guthrie, The Greek Philosophers (London: Methuen, 1950), 73–75.

- ^ Terence Irwin, The Development of Ethics, vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2007), 14

- ^ Gerasimos Santas, "The Socratic Paradoxes", Philosophical Review 73 (1964): 147–64, 147.

- ^ Apology of Socrates 21d.

- ^ John M. Cooper, ed., Complete Works, by Plato (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997), v–vi, viii–xii, 1634–35.

- ^ Cooper, ed., Complete Works, by Plato, v–vi, viii–xii.

- ^ Leo Strauss, The City and Man (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), 50–51.

- ^ Leo Strauss, "Plato", in History of Political Philosophy, ed. Leo Strauss and Joseph Cropsey, 3rd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1987): 33–89.

- ^ Carnes Lord, Introduction to The Politics, by Aristotle (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984): 1–29.

- ^ Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1972).

- ^ Aristotle, Politics, bk. 2, ch. 1–6.

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysics, 991a20–22.

- ^ Robin Smith, "Aristotle's Logic," Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2007).

- ^ Lindberg, David. (1992) The Beginnings of Western Science. University of Chicago Press. p. 162.

- ^ Ann Christy, Christians in Al-Andalus: 711–1000, (Curzon Press, 2002), 142.

- ^ Libraries, Claude Gilliot, Medieval Islamic Civilization: L–Z, Index, ed. Josef W. Meri, Jere L. Bacharach, (Routledge, 2006), 451.