Kronik obstrüktif akciğer hastalığı

| Kronik obstrüktif akciğer hastalığı | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sigara içme durumunda tipik olarak görülen santrilobüler tip amfizemde, akciğerin gros patolojisi. Bu kesilmiş fiksajın yakından görünümünde, boşluklara dolmuş yoğun noktasal siyah karbon tortuları görülmektedir. | |

| Uzmanlık | Göğüs hastalıkları |

Kronik obstrüktif akciğer hastalığı (KOAH), zayıf hava akışının görüldüğü obstrüktif bir akciğer hastalığıdır. Tipik olarak zamanla daha kötüleşir. Ana belirtileri nefes darlığı, öksürme ve balgam üretimidir.[1] Kronik bronşit sahibi insanların çoğu aynı zamanda KOAH hastasıdır.[2]

Tütün içiciliği hastalığın en temel nedeni olup hava kirliliği ve genetik gibi daha az etkili nedenleri de vardır.[3] Gelişmekte olan ülkelerde, hava kirliliğinin en etkili nedenlerinden biri doğru havalandırılmamış yemek pişirme ve ısıtma ateşi dumanıdır. Bu tahriş edici şeylere uzun süreli maruz kalmalar, akciğerlerde iltihaplanmaya neden olarak küçük hava yollarının daralmasına ve amfizem adı verilen doku parçalanmasına yol açar.[4] Teşhis, zayıf hava akışını kontrol eden akciğer fonksiyon testleri ile anlaşılır.[5] Astımdan farklı olarak, KOAH hastalarında hava akışı herhangi bir ilaç yardımıyla belirgin bir şekilde düzelemez.

KOAH, bilinen nedenlere maruz kalınımı düşürerek önlenebilir. Bunlar arasında sigara içme oranlarını azaltmak ve iç/dış hava kalitesini yükseltmek gösterilebilir. KOAH tedavisi, sigarayı bırakma, aşılar, rehabilitasyon, düzenli aralıklarla içe çekilen bronkodilatörler ve steroitler yoluyla sağlanır. Bazı insanlar, uzun süreli oksijen terapisi veya akciğer nakliyle belirgin iyileşmeler gösterebilir.[4] Akut kötüleşme periyotları gösteren hastalarda, artan oranlarda ilaç ve hastane altında gözetim gerekebilir.

Dünya çapında KOAH, 329 milyon insanı (dünya nüfusunun %5'i) etkilemektedir. 2012'de 3 milyon insanın ölümüne sebebiyet vererek, dünyadaki en ölümcül üçüncü hastalık olarak tanımlandı.[6] Ölümlerin, yükselen sigara kullanımı ve bazı ülkelerdeki yaşlanan nüfus nedeniyle daha da artacağı öngörülmektedir.[7] 2010'da hastalığın 2.1 trilyon dolarlık bir ekonomik zarara yol açtığı tahmin edildi.[8]

Belirtiler

|

|

| Dinlerken sorun mu yaşıyorsunuz? Medya yardımı alın. | |

KOAH'ın en belirgin belirtisi balgam üretimi, nefes darlığı ve sık öksürmelerdir.[9] Bu belirtiler, uzun sürelere yayılmış bir şekilde görülür[2] ve tipik olarak zamanla kötüleşir.[4] KOAH'ın farklı tiplerinin olup olmadığı kesinleştirilmiş değildir.[3] Önceden amfizem ve kronik bronşit olarak ayrılan hastalıkta, amfizem aslında bir hastalıktan ziyade akciğerdeki değişimleri belirtmek adına kullanılır. Kronik bronşit ise, KOAH hastalığına eşlik edip etmeyeceği kesin olmayan, sadece bazı belirtileri açıklayan bir terimdir.[1]

Öksürme

Kronik öksürmeler gözlenebilen ilk belirtilerdir. İki yıldan uzun bir sürede, yılda üç aydan fazla süren ve balgam üretiminin eşlik ettiği durum, fazladan herhangi bir açıklama yapılmadığı sürece kronik bronşit tanımına dahil olur. Bu durum, KOAH tamamen başlamadan önce de görülebilir. Üretilen balgam miktarı, saatler veya günler arasında farklılık gösterebilir. Bazı durumlarda, öksürük görülmeyebilir ve sıklıkla gözlenmeyen bir biçimde rastlanılabilir. Bazı insanlar bu belirtileri sigaraya atfederler. Balgam, toplumsal ve kültürel koşullara göre yutulup tükürülebilir. Kuvvetli öksürmeler kaburga kırılması veya kısa süreli bilinç kaybına sebebiyet verebilir. KOAH tanısı konulan insanların genelde uzun süren "nezle" geçmişleri vardır.[9]

Nefes kesilmesi

Nefes darlığı hastaların en çok şikayet ettiği belirtidir.[10] Bu durum sıklıkla şöyle tanımlanır: "zorlukla nefes alıyorum", "nefesim kesiliyor" veya "yeterince hava alamıyorum".[11] Ancak farklı terimler farklı kültürlerde kullanılabilir.[9] Tipik olarak nefes darlığı, uzun süreli güç harcama durumlarında daha kötü bir hal alır ve zamanla kötüleşir.[9] İleri vakalarda dinlenme sırasında da gözlenebilir ve sürekli gözlenebilir.[12][13] Bu durum, KOAH hastalarının endişe duyduğu ve hayat kalitesini düşüren en başlıca belirtidir.[9] Daha ileri düzey KOAH hastaları büzülmüş dudaklarından nefes alır ve bu bazı durumlarda nefes darlığını iyileştirebilir.[14][15]

Diğer belirtiler

KOAH hastalarında nefes vermek nefes almaktan uzun sürebilir[16] Göğüs sıkışması görülebilir[9] ancak çok yaygın değildir ve başka bir durumdan dolayı kaynaklanabilir.[10] Nefes yolları engellenmiş hastalar hırıldayabilir veya nefes alırken stetoskoba daha az ses verebilir.[16] Fıçı göğüs de KOAH hastalığının karakteristik belirtisidir ancak görece daha az rastlanır.[16] Tripod pozisyonu hastalık kötüleştikçe gözlenebilir.[2]

İleri düzey KOAH, akciğer arterlerinde yüksek basınca neden olabilir ve bu nedenle kalbin sağ karıncığına baskı uygulayabilir.[4][17][18] Cor pulmonale olarak adlandırılan bu durum, bacak şişmesine [9] ve şişen boyun damarına neden olabilir.[4] KOAH, diğer bütün akciğer hastalıklarından daha büyük bir cor pulmonale tetikleyicisidir.[17] Ancak, cor pulmonale, oksijen tedavisinin kullanımından beri daha az yaygındır.[2]

KOAH, daha çok paylaşılan risk faktörleri nedeniyle, diğer bazı durumlarla beraber gerçekleşir.[3] Bunlar arasında koroner arter hastalığı, yüksek kan basıncı, diyabet, kas yıkımı, osteoporoz, akciğer kanseri, anksiyete bozukluğu ve depresyon yer alır.[3] Ciddi hastalıkları olan insanlarda hâlsizlik yaygın görülür.[9] Çomak parmak, KOAH'ya özgü değildir ve altta yatan bir akciğer kanseri için araştırmaları tetiklemelidir.[19]

Alevlenme

Akut alevlenme, KOAH hastası bireylerde görülen, artan nefes kesilmeleri, artan balgam üretimi, balgamın temizden yeşil/sarı renge dönmesi, öksürüklerin artması olarak tanımlanabilir.[16] Bu durum, yükselen soluk almanın bulgularına da eşlik edebilir: hızlı nefes alma, yüksek kalp hızı, terleme, etkin solunum kası kullanımı, derinin mavileşmesi, konfüzyon veya ciddi alevlenmelerde görülen hırçın davranışlar.[16][20] Stetoskopla yapılan incelemelerde akciğer üstünden ral duyulabilir.[21]

Nedenleri

KOAH'ın en temel nedeni tütün kullanımıdır. Bunun yanında, bazı ülkelerde mesleki nedenlerle beliren maruz kalmalar ve hava kirliliği de sebep olarak gösterilmektedir.[1] Tipik olarak bu semptomların oluşabilmesi için, maruz kalmanın birkaç on-yıl öncesinde olmuş olması gerekir.[1] İnsanların genetik yatkınlığı da hastalığa katkıda bulunabilir.[1]

Tütün kullanımı

Küresel olarak KOAH'ın bir numaralı risk faktörü tütün kullanımıdır.[1] Tütün kullanan insanların %20'si KOAH hastalığına yakalanır.[23] Ancak hayat boyu tütün kullananlar için bu oran %50'lere yükselir.[24] ABD ve Birleşik Krallık'ta, KOAH hastalarının %80-95 kadarı ya tütün kullanıcısıdır ya da hayatlarının bir kısmında tütün kullanmıştır.[23][25][26] Hastalığa yakalanma riski toplam tütün kullanım süresiyle doğru orantılı olarak artmaktadır.[27] Ek olarak, kadınlar erkeklere oranla tütünün zararlarına karşı daha büyük hassasiyet gösterirler.[26] Tütün kullanmayanlarlarda pasif içiciler durumların %20'sini oluştururlar.[25] Marijuana, puro, nargile gibi diğer benzer kullanımlar da risk barındırır.[1] Hamilelik sırasında tütün kullanan kadınlar çocuklarındaki KOAH riskini arttırabilirler.[1]

Hava kirliliği

Kömür veya odun ve tezek gibi biyoyakıtlarla yakılan pişirme ateşleri kötü havalandırıldığında mahal havası kalitesini düşürür. Bu durum gelişmekte olan ülkelerde KOAH'ın en temel sebeplerinden biridir.[28] Bu tip ateşler, neredeyse 3 milyar insan için pişirme ve ısınma kaynağı olup maruz kalma oranları daha yüksek olduğu için özellikle kadınlar için risk oluşturur.[1][28] Bu kullanım, Hindistan, Çin ve Sahraaltı Afrika'daki evlerin %80'inin enerji kaynağıdır.[29]

Şehirlerde yaşayan insanların, kırsal alanlarda yaşayan insanlara oranla KOAH'a yakalanma oranı daha yüksektir.[30] Kentsel hava kirliliği alevlenmeler için katkı sağlayan bir faktör olup hastalığa neden olmadaki rolü kesinlik kazanmamıştır.[1] Egzoz gazı kaynaklı olanlar da dahil olmak üzere, kötü hava kalitesi olan yerlerde KOAH oranları daha yüksektir.[29] Tüm bunlara rağmen bu faktörlerin, tütün kullanımına oranlar daha düşük risk taşıdığına inanılmaktadır.[1]

Mesleki maruz

İş yeri kaynaklı tozlar, kimyasallar ve dumanlara yoğun ve uzun süre maruz kalmak, tütün kullanan veya kullanmayan herkes için KOAH riskini yükseltir.[31] Mesleki maruzun, toplam vakaların %10-20'sine sebep olduğuna inanılmaktadır.[32] ABD'de bu şartların tütün kullanmamış KOAH hastalarının %30'undan fazlasına neden olduğu, yeterli yasaların olmadığı ülkelerde bunun daha da yükseldiği belirtilmektedir.[1]

Bazı sanayiler ve kaynakların hastalıkla bağlantılı olduğu gösterilmiştir:[29] kömür madeni tozu, altın madenciliği, pamuk tekstil sanayi, kadmiyum ve izosiyanat içeren uğraşlar, kaynak dumanları vb.[31] Tarımla ilgili işler de risk taşır.[29] Bazı mesleklerin sahip olduğu risk, yarım ila iki paket sigara tüketiminin verdiği riskle eşdeğer gösterilir.[33] Silika tozuna maruz kalmak da, silikozis riskinden bağımsız olarak KOAH ile sonuçlanabilr.[34] Toz ve sigaraya kalınan maruzun olumsuz etkileri aditif veya muhtemelen aditiften de fazladır.[33]

Genetik

KOAH gelişiminde genetiğin rolü vardır.[1] Akrabalarından KOAH hastası olan tütün kullanıcılarının, olmayan tütün kullanıcılarına göre hastalığa yakalanma riski daha yüksektir.[1] Şimdilik, açık bir şekilde kalıtsal olarak aktarılan risk faktörü AAT'dir.[35] Bu risk, AAT kusurlu olan ve tütün kullanan bireylerde daha da yüksektir.[35] Bu, tüm vakaların %1–5'inin nedenidir[35][36] ve durum 10.000 kişiden 3-4 kişide görülür.[2] Diğer genetik faktörler araştırılmaktadır[35] ve çok olduğu öngörülmektedir.[29]

Diğer

Bazı diğer etmenler, KOAH ile daha yakından alakalıdır. Risk, yoksul insanlar için daha yüksektir. Ancak bunun doğrudan yoksullukla mı, yoksa yoksulluğun yol açtığı diğer etmenlerle (hava kirliliği, yetersiz beslenme) mi ilgili olduğu kesin değildir.[1] Astım veya solunum yolu hiperaktivitesi olan insanlarda yükselen KOAH oranları olduğuna dair bulgular bulunmaktadır.[1] Düşük doğum ağırlığı gibi doğumsal etmenler, KOAH ve bazı enfeksiyon hastalıklarına yakalanma riskini arttırır.[1] Zatürre gibi solunum enfeksiyonlarının, en azından yetişkinler için, KOAH ile yakından bir ilişkisi olmadığı görülmektedir.[2]

Alevlenme

Akut alevlenme (semptomların aniden kötüleşmesi),[37] sıklıkla enfeksiyonlar, çevresel kirleticiler ve hatta yanlış ilaç kullanımıyla tetiklenebilir.[38] Vakaların %50 ila 75'inin enfeksiyonlarla tetiklendiği görülmektedir[38][39] (bakterili olanlar %25, viral olanlar %25, ikisi birden %25).[40] Çevresel kirleticiler arasında kötü iç veya dış hava kalitesi yer alır.[38] Kişisel veya pasif olarak tütün dumanı da riski arttırır.[29] Alevlenme dönemlerinin daha çok kışın olduğu düşünüldüğünde soğuk havanın da tetikleyebileceği görülmektedir.[41] Altta yatan ağır hastalıklara sahip hastalar, alevlenmeyi daha sık yaşar: hafif hastalıklarda yılda 1,8 kez, orta derecedeki hastalıklarda yılda 2 ila 3 kez ve ağır hastalıklarda yılda 3,4 kez.[42] Sık alevlenme yaşayanlarda akciğer işlevi daha hızlı oranlarda kayba uğrar.[43] Pulmoner emboli (akciğerdeki kan pıhtıları) KOAH sahibi hastaların durumunu daha da kötüleştirir.[3]

Patofizyoloji

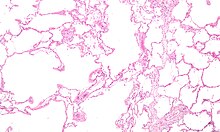

KOAH, kronik olarak havanın kesintili olarak iletildiği (solunum yolu sınırlanımı) ve tamamen nefes vermenin mümkün olmadığı (hava kapanı) bir obstrüktif akciğer hastalığıdır.[3] Zayıf hava akışı, akciğer dokusunda beliren yıkım (amfizem) ve obstrüktif bronşiyolit olarak bilinen küçük solunum yolu hastalığından kaynaklanmaktadır. Bu etmenlerin hastalığa katkısı kişiden kişiye değişiklik gösterebilir.[1] Küçük solunum yolundaki ciddi yıkımlar, akciğer dokusunun yerine büyük hava ceplerinin—bül olarak bilinir— oluşumuna neden olabilir. Hastalığın bu tipi büllöz veya kabarcıklı amfizem olarak adlandırılır.[44]

KOAH, ciğere çekilen tahriş ediciler sonucu kronik yangısal bir hastalık olarak gelişir.[1] Kronik bakteriyel enfeksiyonlar da bu yangısal duruma eklenebilir.[43] Yangısal hücreler, beyaz kan hücrelerinden ikisi olan nötrofil granülositler ve makrofajlar içerebilir. Tütün kullanan hastalarda Tc1 lenfosit görülebilirken, bazı hastalarda astımdakine benzer bir şekilde eozinofile rastlanabilir. Bu hücresel yanıtların bir kısmı yangısal mediyatörler kemotaktik etmenler nedeniyle tetiklenir. Akciğer yıkımıyla ilintili diğer süreçler arasında, tütün kullanımından kaynaklanan yüksek yoğunlukta serbest radikallerin yol açtığı oksidatif stres ve akciğerlerdeki bağ dokunun proteaz inhibitörleri tarafından yetersizce durdurulan proteazlar tarafından yıkımı yer alır. Bağ dokunun yıkımı, amfizeme sebep olan sebeptir ve bu durum zayıf hava akışına ve en sonunda solunum gazlarının zayıf olarak emilip serbest bırakılmasına katkıda bulunur.[1] Hastalıkta gerçekleşen kas yıkımı, akciğerler tarafından kana salınan yangısal mediyatörler sebebiyle gerçekleşebilir.[1]

Solunum kanallarının daralması, yangı ve yara oluşumu sebebiyle gerçekleşir. Bu durum tamamen nefes verememeyle sonuçlanır. Hava akışı sırasında en büyük akış düşüşü, nefes verme sırasında gerçekleşir. Bunun sebebi, nefes verme sırasında göğüste oluşan basıncın hava yollarını baskılamasıdır.[45] Akciğerde önceki nefes verilmeden yeni nefes alınması, akciğerlerin toplamda daha büyük hacimde hava barındırmasına yol açar. Bu durum hiperenflasyon veya hava kapanı olarak adlandırılır.[45][46] Egzersiz sırasındaki hiperenflasyon KOAH'taki nefes kesilmesiyle ilişkilidir çünkü akciğerlerde halen bir miktar hava varken daha fazla hava almaya çalışmak rahatsızlık verir.[47]

Bazı hastalarda, astıma benzer bir şekilde, tahriş edicilere karşı aşırı solunum duyarlılığı görülür.[2]

Tıkalı solunum yolundan kaynaklanan azalan havalanımdan kaynaklanan düşük oksijen düzeyi ve en sonunda kanda yükselen karbon dioksit değerleri ile hiperenflasyon ve nefes alma isteksizliği görülebilir.[1] Alevlenmeler sırasında solunum yanıgısı da yükselir. Bu durum aynı şekilde hiperenflasyonuna ve azalan solunum gazı değiş tokuşuna yol açar. Bu durumun sebep olduğu düşük kan oksijen seviyeleri, uzun süre devam ettiği takdirde vazokonstrüksiyon adı verilen kan damarı daralmalarına; amfizem ise akciğerlerdeki kılcal damarların yıkımına yol açabilir.[4] Bu iki değişiklik de pulmoner arterde kan basıncını yükseltir ve cor pulmonale'ye neden olur.[1]

Tanı

35 ila 40 yaş üzerinde, nefes darlığı çeken, kronik öksüren, balgam üreten, kışları sıkça soğuk algınlığına yakalanan, risk etmenleriyle bir geçmişi bulunan insanlarda KOAH aranabilir.[9][10] Spirometri tanıyı onaylamak için kullanılır.[9][48]

Spirometri

Spirometre, var olan hava akışı tıkanıklığını ölçer ve hava yolunu açmak adına bronkodilatör türevi ilaçların kullanımından sonra uygulanır.[48] Tanı yapmak için iki ölçüt vardır: bir saniye içinde zorlanan nefes verme hacmi (FEV1) ve tek bir nefeste verilen en büyük hava hacmini tanımlamak için kullanılan zorlanan nefes gücüdür (FVC).[49] Normal olarak, semptomları gösteren birinde FVC değerinin %75–80'i ilk saniyede ortaya çıkması[49] ve FEV1/FVC oranının %70'ten az çıkması bu kişinin KOAH hastası olduğunu kanıtlar.[48] Bu ölçümlerden yola çıkarak, spirometri yaşlı insanlarda KOAH için aşırı-tanıya yol açabilir.[48] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence kriterleri, bunların yanında tahmin edilenin %80'inden az bir FEV1 oranı da gerektirir.[10]

Spirometrinin KOAH semptomları göstermeyen bireylerde, tarama amacıyla kullanılmasının etkileri bilinmemektedir ve şimdilik önerilmemektedir.[9][48] Astım için sıkça kullanılan zirve akım hızı (maksimum solunum hızı), KOAH tanısı için yeterli değildir.[10]

Şiddet

| Derece | Etki eden aktivite |

|---|---|

| 1 | Ağır iş |

| 2 | Hareketli yürüyüş |

| 3 | Normal yürüyüş |

| 4 | Birkaç dakikalık yürüyüş |

| 5 | Kıyafet değiştirmek |

| Şiddet | FEV1 % tahmin edilen |

|---|---|

| Hafif (GOLD 1) | ≥80 |

| Orta (GOLD 2) | 50–79 |

| Şiddetli (GOLD 3) | 30–49 |

| Çok şiddetli (GOLD 4) | <30 or kronik solunum yetmezliği |

KOAH'ın belirli bir hastayı ne kadar eklediğini anlamak için çeşitli yöntemler mevcuttur.[9] Düzeltilmiş Britanya Tıp Araştırma Konseyi anketi (mMRC) veya KOAH değerlendirme testi (CAT) semptomların şiddetini belirlemek için yapılan basit anketlerdir.[9] 0 ile 40 arasında değişen CAT skalasında sayı arttıkça hastalığın şiddeti artar.[50] Spirometri hava akış sınırlamasını belirlemeye yardımcı olabilir.[9] Bu genel olarak, kişinin yaşı, cinsiyeti, boyu ve ağırlığına göre tahmin edilen "normal"e kıyasla FEV1 değerlerinin yüzdesi olarak belirtilir.[9] Hem Amerikan hem Avrupa ana esasları, tedavi için kısmi önerileri FEV1 üzerinden yapar.[48] GOLD esasları ise, insanları hava akışı sınırlamalarına göre dört kategoriye ayırmayı önerir.[9] Kilo kaybı, kas güçsüzlüğü ve diğer hastalıkların varlığı da hesaba katılmalıdır.[9]

Diğer testler

Göğüs radyografisi ve hemogram kullanımı, tanı sırasındaki diğer şartları hariç tutmak adına yapılabilir.[51] X ışını sonuçlarında genel olarak göze çarpan durumlar, olağandan büyük akciğerler, düzleşmiş diyafram, yükselen göğüs kemiği arkası hava boşluğu ve bül görülebilir. Bu sayede zatürre, pulmoner ödem veya pnömotoraks gibi durumlar hariç tutulabilir.[52] Göğüs için yapılan yüksek çözünürlüklü bir bilgisayarlı tomografi taraması akciğerlerdeki amfizemin bulunduğu yerleri teşhis etmekte kullanılır ve diğer hastalıkları hariç tutmak adına yararlıdır.[2] Yine de, ameliyat planlanmadığı sürece bu durum yönetim konusunda nadiren katkı sağlar.[2] Kan gazı analizi oksijen ihtiyacını belirlemek için kullanılır ve FEV1 değeri tahmin edilenin %35'inden az olan hastalara, çevresel oksijen doyumu %92'den az olanlara ve konjestif kalp yetmezliği belirtileri gösterenlere uygulanır.[9] Alfa-1 antitripsin eksikliğinin yoğun olduğu ülkelerde (özel olarak 45 yaş altı olan ve amfizemlerin akciğerin alt kısımlarında bulunduğu bireylerde) KOAH hastaları test edilmelidir.[9]

-

Göğüs röntgeninde açığa çıkan şiddetli KOAH. Akciğere oranla küçük kalan kalbe dikkat ediniz.

-

Amfizemli bir hastanın yandan röntgen görüntüsü. Fıçılaşmış göğsü ve düz diyaframa dikkat etiniz.

-

Şiddetli KOAH hastası birinin CXR görüntüsünde görülen uzun büller.

-

Şiddetli bir hastada büllü amfizem.

-

Son aşamasında büllü amfizemi olan hastanın eksenel CT görüntüsü.

Ayırıcı tanı

KOAH, nefes darlığına sebep olan diğer hastalıklardan ayırt edilmelidir. Bu hastalıklar arasında konjestif kalp yetmezliği, pulmoner damar tıkanıklığı, zatürre veya pnömotoraks yer alır. Birçok KOAH hastası astım olduğunu düşünür.[16] İkisi arasındaki ayrım, semptomlara göre yapılır. Buna göre tütün kullanım geçmişine, spirometride hava akışı sınırlanışının bronkodilatör kullanımıyla geri döndürülebilir olmasına bakılır.[53] Verem, kronik öksürme ile belirebildiği için, özellikle hastalığın görüldüğü yerlerde dikkate alınmalıdır.[9] Daha nadir de olsa, benzer etkiler gösteren bronkopulmoner displazi ve bronşiyolitis obliterans gibi hastalıklardan ayırt edilmelidir.[51] Kronik bronşit de normal hava akışı ile gerçekleşebilir ve bu durumda KOAH olarak sınıflandırılmaz.[2]

Önlem

KOAH'nın pek çok tipi potansiyel olarak dumana maruzu azaltarak ve hava kalitesini artırarak önlenebilmektedir.[29] Yıllık grip aşısı uygulaması sayesinde ataklar, hastaneye yatırılma ve ölüm gibi durumların olasılığı düşürülmektedir.[54][55] Pnömokok aşıları da yarar sağlayabilmektedir.[54]

Sigarayı bırakma

KOAH'nın önüne geçmenin en temel yolu insanların sigara alışkanlığı edinmesinin önüne geçmektir.[56] Hükümetlerin, toplumsal sağlık kuruluşları ve sigara-karşıtı organizasyonların alacağı tedbirler sayesinde insanların sigaraya başlama ve sigarayı teşvik etme eğilimleri azaltılabilir.[57] Halka açık mekanlarda ve iş yerlerinde sigara yasağı uygulaması ile pasif içicilikten kaynaklanan sorunların önüne geçilebilir.[29]

Sigara kullanan kimselerde sigarayı bırakmak, KOAH'nın daha kötüleşmesinin önüne geçmek için yapılabilecek tek önlemdir.[58] Hastalığın son dönemlerinde dahi, bu uygulamayla akciğer işlevinin kötüleşme hızı azaltılabilir ve engellilik, ölüm gibi durumların geciktirilmesi sağlanabilir.[59] Sigarayı bırakmak, karar vermekle başlar. Uzun dönem bırakış genellikle birkaç deneme sonrasında başarıya ulaşır.[57] 5 yıldan fazla çaba gösteren insanların yaklaşık %40'ında başarı görülür.[60]

Bazı içiciler, sadece iradeyle uzun dönem sigarayı bırakabilirler. Ancak oldukça bağımlılık yapan bir etkinlik olduğundan,[61] sigarayı bırakmak isteyen kimselerin ek desteğe ihtiyaçları vardır. Sigarayı bırakma ihtimali, çevreden gelen destek, sigara bırakma programlarına katılım ve/veya nikotin replasman tedavisi, bupropiyon veya vareniklin gibi ilaçların kullanılmasıyla artırılabilir.[57][60]

Meslek sağlığı

Kömür madenciliği, inşaat işçiliği ve taş işçiliği gibi risk altındaki meslek gruplarının KOAH'a yakalanma oranını azaltmak adına bazı önlemler alınagelmiştir.[29] Bu önlemler arasında şöyle örnekler yer alır: kamu politikası üretimi,[29] işçilerin riskler konusunda eğitimi ve yönetimi, sigarayı bırakma konusunda destek, işçilerin erken KOAH belirtisi konusunda kontrol edilmesi, gaz maskesi kullanımı ve toz kontrolü.[62][63] Havalandırmayı geliştirmek, su spreyleri kullanmak ve toz üretimini düşüren madencilik tekniklerini uygulamak, etkili bir toz kontrolü sağlar.[64] Bir işçi KOAH'a yakalanırsa, işçinin iş rolünü değiştirmek gibi yollarla toza maruzu azaltılabilir ve hastalığın ciddileşmesinin önüne geçilebilir.[65]

Hava kirliliği

Hem iç hem dış mekanlarda hava kalitesi yükseltilerek KOAH'ın önüne geçilebilir veya var olan hastalığın kötüleşmesinin önüne geçilebilir.[29] Bu durum, kamu politikası çabalarıyla ve kişisel dahiliyet ile başarılabilir.[66]

Bazı gelişmiş ülkeler, bazı düzenlemelere giderek dış mekanlarındaki hava kalitesini yükseltmiştir. Bu sayede nüfuslarının KOAH geliştirme oranlarında olumlu değişimlere yol açmıştır.[29] KOAH hastası insanlar, dış mekandaki hava kalitesinin kötü olduğu durumlarda iç mekanlarda kalarak semptomlar gösterme ihtimallerini düşürebilirler.[4]

Bir diğer önlem, yemek pişirilen veya ısıtılan mekanlarda görülen yakıt dumanının, etkili havalandırma, hatta daha iyi soba ve bacalar kullanılarak azaltılmasıdır.[66] Düzgün sobala kullanımı, iç mekan hava kalitesini %85'e kadar iyileştirir. Güneş enerjisiyle yemek pişirme ve ısıtma gibi alternatif enerji kaynaklarının kullanımı, hatta biyokütle (tezek/odun) yerine kömür/gazyağı gibi yakıtların kullanımı, daha iyi sonuçlar doğurmaktadır.[29]

Yönetim

There is no known cure for COPD, but the symptoms are treatable and its progression can be delayed.[56] The major goals of management are to reduce risk factors, manage stable COPD, prevent and treat acute exacerbations, and manage associated illnesses.[4] The only measures that have been shown to reduce mortality are smoking cessation and supplemental oxygen.[67] Stopping smoking decreases the risk of death by 18%.[3] Other recommendations include influenza vaccination once a year, pneumococcal vaccination once every 5 years, and reduction in exposure to environmental air pollution.[3] In those with advanced disease, palliative care may reduce symptoms, with morphine improving the feelings of shortness of breath.[68] Noninvasive ventilation may be used to support breathing.[68]

Egzersiz

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a program of exercise, disease management and counseling, coordinated to benefit the individual.[69] In those who have had a recent exacerbation, pulmonary rehabilitation appears to improve the overall quality of life and the ability to exercise, and reduce mortality.[70] It has also been shown to improve the sense of control a person has over their disease, as well as their emotions.[71] Breathing exercises in and of themselves appear to have a limited role.[15]

Being either underweight or overweight can affect the symptoms, degree of disability and prognosis of COPD. People with COPD who are underweight can improve their breathing muscle strength by increasing their calorie intake.[4] When combined with regular exercise or a pulmonary rehabilitation program, this can lead to improvements in COPD symptoms. Supplemental nutrition may be useful in those who are malnourished.[72]

Bronkodilatörler

Inhaled bronchodilators are the primary medications used[3] and result in a small overall benefit.[73] There are two major types, β2 agonists and anticholinergics; both exist in long-acting and short-acting forms. They reduce shortness of breath, wheeze and exercise limitation, resulting in an improved quality of life.[74] It is unclear if they change the progression of the underlying disease.[3]

In those with mild disease, short-acting agents are recommended on an as needed basis.[3] In those with more severe disease, long-acting agents are recommended.[3] If long-acting bronchodilators are insufficient, then inhaled corticosteroids are typically added.[3] With respect to long-acting agents, it is unclear if tiotropium (a long-acting anticholinergic) or long-acting beta agonists (LABAs) are better, and it may be worth trying each and continuing the one that worked best.[75] Both types of agent appear to reduce the risk of acute exacerbations by 15–25%.[3] While both may be used at the same time, any benefit is of questionable significance.[76]

There are several short-acting β2 agonists available including salbutamol (Ventolin) and terbutaline.[77] They provide some relief of symptoms for four to six hours.[77] Long-acting β2 agonists such as salmeterol and formoterol are often used as maintenance therapy. Some feel the evidence of benefits is limited[78] while others view the evidence of benefit as established.[79][80] Long-term use appears safe in COPD[81] with adverse effects include shakiness and heart palpitations.[3] When used with inhaled steroids they increase the risk of pneumonia.[3] While steroids and LABAs may work better together,[78] it is unclear if this slight benefit outweighs the increased risks.[82]

There are two main anticholinergics used in COPD, ipratropium and tiotropium. Ipratropium is a short-acting agent while tiotropium is long-acting. Tiotropium is associated with a decrease in exacerbations and improved quality of life,[76] and tiotropium provides those benefits better than ipratropium.[83] It does not appear to affect mortality or the over all hospitalization rate.[84] Anticholinergics can cause dry mouth and urinary tract symptoms.[3] They are also associated with increased risk of heart disease and stroke.[85][86] Aclidinium, another long acting agent which came to market in 2012, has been used as an alternative to tiotropium.[87][88]

Kortikosteroitler

Corticosteroids are usually used in inhaled form but may also be used as tablets to treat and prevent acute exacerbations. While inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) have not shown benefit for people with mild COPD, they decrease acute exacerbations in those with either moderate or severe disease.[89] When used in combination with a LABA they decrease mortality more than either ICS or LABA alone.[90] By themselves they have no effect on overall one-year mortality and are associated with increased rates of pneumonia.[67] It is unclear if they affect the progression of the disease.[3] Long-term treatment with steroid tablets is associated with significant side effects.[77]

Diğer ilaçlar

Long-term antibiotics, specifically those from the macrolide class such as erythromycin, reduce the frequency of exacerbations in those who have two or more a year.[91][92] This practice may be cost effective in some areas of the world.[93] Concerns include that of antibiotic resistance and hearing problems with azithromycin.[92] Methylxanthines such as theophylline generally cause more harm than benefit and thus are usually not recommended,[94] but may be used as a second-line agent in those not controlled by other measures.[4] Mucolytics may be useful in some people who have very thick mucus but are generally not needed.[54] Cough medicines are not recommended.[77]

Oksijen

Supplemental oxygen is recommended in those with low oxygen levels at rest (a partial pressure of oxygen of less than 50–55 mmHg or oxygen saturations of less than 88%).[77][95] In this group of people it decreases the risk of heart failure and death if used 15 hours per day[77][95] and may improve people's ability to exercise.[96] In those with normal or mildly low oxygen levels, oxygen supplementation may improve shortness of breath.[97] There is a risk of fires and little benefit when those on oxygen continue to smoke.[98] In this situation some recommend against its use.[99] During acute exacerbations, many require oxygen therapy; the use of high concentrations of oxygen without taking into account a person's oxygen saturations may lead to increased levels of carbon dioxide and worsened outcomes.[100][101] In those at high risk of high carbon dioxide levels, oxygen saturations of 88–92% are recommended, while for those without this risk recommended levels are 94–98%.[101]

Cerrahi

For those with very severe disease surgery is sometimes helpful and may include lung transplantation or lung volume reduction surgery.[3] Lung volume reduction surgery involves removing the parts of the lung most damaged by emphysema allowing the remaining, relatively good lung to expand and work better.[77] Lung transplantation is sometimes performed for very severe COPD, particularly in younger individuals.[77]

Ataklar

Acute exacerbations are typically treated by increasing the usage of short-acting bronchodilators.[3] This commonly includes a combination of a short-acting inhaled beta agonist and anticholinergic.[37] These medications can be given either via a metered-dose inhaler with a spacer or via a nebulizer with both appearing to be equally effective.[37] Nebulization may be easier for those who are more unwell.[37]

Oral corticosteroids improve the chance of recovery and decrease the overall duration of symptoms.[3][37] They work equally well as intravenous steroids but appear to have fewer side effects.[102] Five days of steroids work as well as ten or fourteen.[103] In those with a severe exacerbation, antibiotics improve outcomes.[104] A number of different antibiotics may be used including amoxicillin, doxycycline and azithromycin; it is unclear if one is better than the others.[54] There is no clear evidence for those with less severe cases.[104]

For those with type 2 respiratory failure (acutely raised CO2 levels) non-invasive positive pressure ventilation decreases the probability of death or the need of intensive care admission.[3] Additionally, theophylline may have a role in those who do not respond to other measures.[3] Fewer than 20% of exacerbations require hospital admission.[37] In those without acidosis from respiratory failure, home care ("hospital at home") may be able to help avoid some admissions.[37][105]

Prognoz

no data ≤110 110–220 220–330 330–440 440–550 550–660 | 660–770 770–880 880–990 990–1100 1100–1350 ≥1350 |

COPD usually gets gradually worse over time and can ultimately result in death. It is estimated that 3% of all disability is related to COPD.[107] The proportion of disability from COPD globally has decreased from 1990 to 2010 due to improved indoor air quality primarily in Asia.[107] The overall number of years lived with disability from COPD, however, has increased.[108]

The rate at which COPD worsens varies with the presence of factors that predict a poor outcome, including severe airflow obstruction, little ability to exercise, shortness of breath, significantly underweight or overweight, congestive heart failure, continued smoking, and frequent exacerbations.[4] Long-term outcomes in COPD can be estimated using the BODE index which gives a score of zero to ten depending on FEV1, body-mass index, the distance walked in six minutes, and the modified MRC dyspnea scale.[109] Significant weight loss is a bad sign.[2] Results of spirometry are also a good predictor of the future progress of the disease but not as good as the BODE index.[2][10]

Epidemiyoloji

Globally, as of 2010, COPD affected approximately 329 million people (4.8% of the population) and is slightly more common in men than women.[108] This is as compared to 64 million being affected in 2004.[110] The increase in the developing world between 1970 and the 2000s is believed to be related to increasing rates of smoking in this region, an increasing population and an aging population due to less deaths from other causes such as infectious diseases.[3] Some developed countries have seen increased rates, some have remained stable and some have seen a decrease in COPD prevalence.[3] The global numbers are expected to continue increasing as risk factors remain common and the population continues to get older.[56]

Between 1990 and 2010 the number of deaths from COPD decreased slightly from 3.1 million to 2.9 million[111] and became the fourth leading cause of death.[3] In 2012 it became the third leading cause as the number of deaths rose again to 3.1 million.[6] In some countries, mortality has decreased in men but increased in women.[112] This is most likely due to rates of smoking in women and men becoming more similar.[2] COPD is more common in older people;[1] it affects 34-200 out of 1000 people older than 65 years, depending on the population under review.[1][52]

In England, an estimated 0.84 million people (of 50 million) have a diagnosis of COPD; this translates into approximately one person in 59 receiving a diagnosis of COPD at some point in their lives. In the most socioeconomically deprived parts of the country, one in 32 people were diagnosed with COPD, compared with one in 98 in the most affluent areas.[113] In the United States approximately 6.3% of the adult population, totaling approximately 15 million people, have been diagnosed with COPD.[114] 25 million people may have COPD if currently undiagnosed cases are included.[115] In 2011, there were approximately 730,000 hospitalizations in the United States for COPD.[116]

Tarih

The word "emphysema" is derived from the Greek Yunanca: ἐμφυσᾶν emphysan meaning "inflate" -itself composed of ἐν en, meaning "in", and φυσᾶν physan, meaning "breath, blastŞablon:-".[117] The term chronic bronchitis came into use in 1808[118] while the term COPD is believed to have first been used in 1965.[119] Previously it has been known by a number of different names, including chronic obstructive bronchopulmonary disease, chronic obstructive respiratory disease, chronic airflow obstruction, chronic airflow limitation, chronic obstructive lung disease, nonspecific chronic pulmonary disease, and diffuse obstructive pulmonary syndrome. The terms chronic bronchitis and emphysema were formally defined in 1959 at the CIBA guest symposium and in 1962 at the American Thoracic Society Committee meeting on Diagnostic Standards.[119]

Early descriptions of probable emphysema include: in 1679 by T. Bonet of a condition of "voluminous lungs" and in 1769 by Giovanni Morgagni of lungs which were "turgid particularly from air".[119][120] In 1721 the first drawings of emphysema were made by Ruysh.[120] These were followed with pictures by Matthew Baillie in 1789 and descriptions of the destructive nature of the condition. In 1814 Charles Badham used "catarrh" to describe the cough and excess mucus in chronic bronchitis. René Laennec, the physician who invented the stethoscope, used the term "emphysema" in his book A Treatise on the Diseases of the Chest and of Mediate Auscultation (1837) to describe lungs that did not collapse when he opened the chest during an autopsy. He noted that they did not collapse as usual because they were full of air and the airways were filled with mucus. In 1842, John Hutchinson invented the spirometer, which allowed the measurement of vital capacity of the lungs. However, his spirometer could only measure volume, not airflow. Tiffeneau and Pinelli in 1947 described the principles of measuring airflow.[119]

In 1953, Dr. George L. Waldbott, an American allergist, first described a new disease he named "smoker's respiratory syndrome" in the 1953 Journal of the American Medical Association. This was the first association between tobacco smoking and chronic respiratory disease.[121]

Early treatments included garlic, cinnamon and ipecac, among others.[118] Modern treatments were developed during the second half of the 20th century. Evidence supporting the use of steroids in COPD were published in the late 1950s. Bronchodilators came into use in the 1960s following a promising trial of isoprenaline. Further bronchodilators, such as salbutamol, were developed in the 1970s, and the use of LABAs began in the mid-1990s.[122]

Toplum ve kültür

COPD has been referred to as "smoker's lung".[123] Those with emphysema have been known as "pink puffers" or "type A" due to their frequent pink complexion, fast respiratory rate and pursed lips,[124][125] and people with chronic bronchitis have been referred to as "blue bloaters" or "type B" due to the often bluish color of the skin and lips from low oxygen levels and their ankle swelling.[125][126] This terminology is no longer accepted as useful as most people with COPD have a combination of both.[2][125]

Many health systems have difficulty ensuring appropriate identification, diagnosis and care of people with COPD; Britain's Department of Health has identified this as a major issue for the National Health Service and has introduced a specific strategy to tackle these problems.[127]

Ekonomi

Globally, as of 2010, COPD is estimated to result in economic costs of $2.1 trillion, half of which occurring in the developing world.[8] Of this total an estimated $1.9 trillion are direct costs such as medical care, while $0.2 trillion are indirect costs such as missed work.[128] This is expected to more than double by the year 2030.[8] In Europe, COPD represents 3% of healthcare spending.[1] In the United States, costs of the disease are estimated at $50 billion, most of which is due to exacerbation.[1] COPD was among the most expensive conditions seen in U.S. hospitals in 2011, with a total cost of about $5.7 billion.[116]

Araştırma

Infliximab, an immune-suppressing antibody, has been tested in COPD but there was no evidence of benefit with the possibility of harm.[129] Roflumilast shows promise in decreasing the rate of exacerbations but does not appear to change quality of life.[3] A number of new, long-acting agents are under development.[3] Treatment with stem cells is under study,[130] and while generally safe and with promising animal data there is little human data as of 2014.[131]

Diğer hayvanlar

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may occur in a number of other animals and may be caused by exposure to tobacco smoke.[132][133] Most cases of the disease, however, are relatively mild.[134] In horses it is also known as recurrent airway obstruction and is typically due to an allergic reaction to a fungus contained in straw.[135] COPD is also commonly found in old dogs.[136]

Ayrıca bakınız

Bibliyografi

- "Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Updated 2013" (PDF). Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 5 Nisan 2015 tarihinde kaynağından (PDF) arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: November 29, 2013.

- Şablon:NICE

- Qaseem, Amir; Wilt, TJ; Weinberger, SE; Hanania, NA; Criner, G; Van Der Molen, T; Marciniuk, DD; Denberg, T; Schünemann, H; Wedzicha, W; MacDonald, R; Shekelle, P; American College Of Physicians; American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society (2011). "Diagnosis and Management of Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society". Annals of Internal Medicine. 155 (3). ss. 179–91. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00008. PMID 21810710.

Kaynakça

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Vestbo, Jørgen (2013). "Definition and Overview" (PDF). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. ss. 1–7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Reilly, John J.; Silverman, Edwin K.; Shapiro, Steven D. (2011). "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease". Longo, Dan; Fauci, Anthony; Kasper, Dennis; Hauser, Stephen; Jameson, J.; Loscalzo, Joseph (Ed.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th bas.). McGraw Hill. ss. 2151–9. ISBN 978-0-07-174889-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M (Nisan 2012). "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Lancet. 379 (9823). ss. 1341–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60968-9. PMID 22314182.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, Zielinski J (Eylül 2007). "Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176 (6). ss. 532–55. doi:10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. PMID 17507545.

- ^ Nathell L, Nathell M, Malmberg P, Larsson K (2007). "COPD diagnosis related to different guidelines and spirometry techniques". Respir. Res. 8 (1). s. 89. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-8-89. PMC 2217523 $2. PMID 18053200.

- ^ a b "The 10 leading causes of death in the world, 2000 and 2011". World Health Organization. July 2013. 2 Ocak 2016 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 29 Kasım 2013.

- ^ Mathers CD, Loncar D (November 2006). "Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030". PLoS Med. 3 (11). ss. e442. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. PMC 1664601 $2. PMID 17132052.

- ^ a b c Lomborg, Bjørn (2013). Global problems, local solutions : costs and benefits. Cambridge University Pres. s. 143. ISBN 978-1-107-03959-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Vestbo, Jørgen (2013). "Diagnosis and Assessment" (PDF). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. ss. 9–17.

- ^ a b c d e f g Şablon:NICE

- ^ Mahler DA (2006). "Mechanisms and measurement of dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 3 (3). ss. 234–8. doi:10.1513/pats.200509-103SF. PMID 16636091.

- ^ "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of COPD?". National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 31 Temmuz 2013. 21 Ekim 2014 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 29 Kasım 2013.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ^ Morrison, [edited by] Nathan E. Goldstein, R. Sean (2013). Evidence-based practice of palliative medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders. s. 124. ISBN 978-1-4377-3796-7.

- ^ a b Holland AE, Hill CJ, Jones AY, McDonald CF (2012). Holland, Anne E (Ed.). "Breathing exercises for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 10. ss. CD008250. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008250.pub2. PMID 23076942.

- ^ a b c d e f Gruber, Phillip (Kasım 2008). "The Acute Presentation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease In the Emergency Department: A Challenging Oxymoron". Emergency Medicine Practice. 10 (11).

- ^ a b Weitzenblum E, Chaouat A (2009). "Cor pulmonale". Chron Respir Dis. 6 (3). ss. 177–85. doi:10.1177/1479972309104664. PMID 19643833.

- ^ "Cor pulmonale". Professional guide to diseases (9th bas.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009. ss. 120–2. ISBN 978-0-7817-7899-2.

- ^ Mandell, editors, James K. Stoller, Franklin A. Michota, Jr., Brian F. (2009). The Cleveland Clinic Foundation intensive review of internal medicine (5th bas.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. s. 419. ISBN 978-0-7817-9079-6.

- ^ Brulotte CA, Lang ES (May 2012). "Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the emergency department". Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 30 (2). ss. 223–47, vii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2011.10.005. PMID 22487106.

- ^ Spiro, Stephen (2012). Clinical respiratory medicine expert consult (4th bas.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4557-2329-4.

- ^ World Health Organization (2008). WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2008: The MPOWER Package (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ss. 268–309. ISBN 92-4-159628-7.

- ^ a b Ward, Helen (2012). Oxford Handbook of Epidemiology for Clinicians. Oxford University Press. ss. 289–290. ISBN 978-0-19-165478-7.

- ^ Laniado-Laborín, R (Ocak 2009). "Smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Parallel epidemics of the 21st century". International journal of environmental research and public health. 6 (1). ss. 209–24. doi:10.3390/ijerph6010209. PMC 2672326 $2. PMID 19440278.

- ^ a b Rennard, Stephen (2013). Clinical management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2nd bas.). New York: Informa Healthcare. s. 23. ISBN 978-0-8493-7588-0.

- ^ a b Anita Sharma ; with a contribution by David Pitchforth ; forewords by Gail Richards; Barclay, Joyce (2010). COPD in primary care. Oxford: Radcliffe Pub. s. 9. ISBN 978-1-84619-316-3.

- ^ Goldman, Lee (2012). Goldman's Cecil medicine (24th bas.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders. s. 537. ISBN 978-1-4377-1604-7.

- ^ a b Kennedy SM, Chambers R, Du W, Dimich-Ward H (Aralık 2007). "Environmental and occupational exposures: do they affect chronic obstructive pulmonary disease differently in women and men?". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 4 (8). ss. 692–4. doi:10.1513/pats.200707-094SD. PMID 18073405.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Pirozzi C, Scholand MB (July 2012). "Smoking cessation and environmental hygiene". Med. Clin. North Am. 96 (4). ss. 849–67. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2012.04.014. PMID 22793948.

- ^ Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, Badamgarav E, Buist AS, Mannino DM (September 2006). "Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis". Eur. Respir. J. 28 (3). ss. 523–32. doi:10.1183/09031936.06.00124605. PMID 16611654.

- ^ a b Devereux, Graham (2006). "Definition, epidemiology and risk factors". BMJ. 332 (7550). ss. 1142–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7550.1142. PMC 1459603 $2. PMID 16690673.

- ^ Laine, Christine (2009). In the Clinic: Practical Information about Common Health Problems. ACP Press. s. 226. ISBN 978-1-934465-64-6.

- ^ a b Barnes, Peter J.; Drazen, Jeffrey M.; Rennard, Stephen I.; Thomson, Neil C., (Ed.) (2009). "Relationship between cigarette smoking and occupational exposures". Asthma and COPD: Basic Mechanisms and Clinical Management. Amsterdam: Academic. s. 464. ISBN 978-0-12-374001-4. Bilinmeyen parametre

|displayeditors=görmezden gelindi (yardım) - ^ Rushton, Lesley (2007). "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Occupational Exposure to Silica". Reviews on Environmental Health. 22 (4). ss. 255–72. doi:10.1515/REVEH.2007.22.4.255. PMID 18351226.

- ^ a b c d Foreman MG, Campos M, Celedón JC (Temmuz 2012). "Genes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Med. Clin. North Am. 96 (4). ss. 699–711. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2012.02.006. PMC 3399759 $2. PMID 22793939.

- ^ Brode SK, Ling SC, Chapman KR (September 2012). "Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: a commonly overlooked cause of lung disease". CMAJ. 184 (12). ss. 1365–71. doi:10.1503/cmaj.111749. PMC 3447047 $2. PMID 22761482.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vestbo, Jørgen (2013). "Management of Exacerbations" (PDF). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. ss. 39–45.

- ^ a b c Dhar, Raja (2011). Textbook of pulmonary and critical care medicine. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. s. 1056. ISBN 978-93-5025-073-0.

- ^ Palange, Paolo (2013). ERS Handbook of Respiratory Medicine. European Respiratory Society. s. 194. ISBN 978-1-84984-041-5.

- ^ Lötvall, Jan (2011). Advances in combination therapy for asthma and COPD. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. s. 251. ISBN 978-1-119-97846-6.

- ^ Barnes, Peter (2009). Asthma and COPD : basic mechanisms and clinical management (2nd bas.). Amsterdam: Academic. s. 837. ISBN 978-0-12-374001-4.

- ^ Hanania, Nicola (2010-12-09). COPD a Guide to Diagnosis and Clinical Management (1st bas.). Totowa, NJ: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. s. 197. ISBN 978-1-59745-357-8.

- ^ a b Beasley, V; Joshi, PV; Singanayagam, A; Molyneaux, PL; Johnston, SL; Mallia, P (2012). "Lung microbiology and exacerbations in COPD". International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cilt 7. ss. 555–69. doi:10.2147/COPD.S28286. PMC 3437812 $2. PMID 22969296.

- ^ Murphy DMF, Fishman AP (2008). "Chapter 53". Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (4th bas.). McGraw-Hill. s. 913. ISBN 0-07-145739-9.

- ^ a b Calverley PM, Koulouris NG (2005). "Flow limitation and dynamic hyperinflation: key concepts in modern respiratory physiology". Eur Respir J. 25 (1). ss. 186–199. doi:10.1183/09031936.04.00113204. PMID 15640341.

- ^ Currie, Graeme P. (2010). ABC of COPD (2nd bas.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, BMJ Books. s. 32. ISBN 978-1-4443-2948-3.

- ^ O'Donnell DE (2006). "Hyperinflation, Dyspnea, and Exercise Intolerance in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease". The Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 3 (2). ss. 180–4. doi:10.1513/pats.200508-093DO. PMID 16565429.

- ^ a b c d e f Qaseem, Amir; Wilt, TJ; Weinberger, SE; Hanania, NA; Criner, G; Van Der Molen, T; Marciniuk, DD; Denberg, T; Schünemann, H; Wedzicha, W; MacDonald, R; Shekelle, P; American College Of Physicians; American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society (2011). "Diagnosis and Management of Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society". Annals of Internal Medicine. 155 (3). ss. 179–91. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00008. PMID 21810710.

- ^ a b Young, Vincent B. (2010). Blueprints medicine (5th bas.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott William & Wilkins. s. 69. ISBN 978-0-7817-8870-0.

- ^ "COPD Assessment Test (CAT)". American Thoracic Society. 19 Ocak 2015 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 29 Kasım 2013.

- ^ a b Şablon:NICE

- ^ a b Torres M, Moayedi S (May 2007). "Evaluation of the acutely dyspneic elderly patient". Clin. Geriatr. Med. 23 (2). ss. 307–25, vi. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2007.01.007. PMID 17462519.

- ^ BTS COPD Consortium (2005). "Spirometry in practice - a practical guide to using spirometry in primary care". ss. 8–9. 13 Nisan 2015 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 25 Ağustos 2014.

- ^ a b c d Mackay AJ, Hurst JR (July 2012). "COPD exacerbations: causes, prevention, and treatment". Med. Clin. North Am. 96 (4). ss. 789–809. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2012.02.008. PMID 22793945.

- ^ Poole PJ, Chacko E, Wood-Baker RW, Cates CJ (2006). Poole, Phillippa (Ed.). "Influenza vaccine for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 1. ss. CD002733. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002733.pub2. PMID 16437444.

- ^ a b c Vestbo, Jørgen (2013). "Introduction". Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (PDF). Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. xiii–xv.

- ^ a b c Policy Recommendations for Smoking Cessation and Treatment of Tobacco Dependence. World Health Organization. ss. 15–40. ISBN 978-92-4-156240-9.

- ^ Jiménez-Ruiz CA, Fagerström KO (March 2013). "Smoking cessation treatment for COPD smokers: the role of counselling". Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 79 (1). ss. 33–7. PMID 23741944.

- ^ Kumar P, Clark M (2005). Clinical Medicine (6th bas.). Elsevier Saunders. ss. 900–1. ISBN 0-7020-2763-4.

- ^ a b Tønnesen P (March 2013). "Smoking cessation and COPD". Eur Respir Rev. 22 (127). ss. 37–43. doi:10.1183/09059180.00007212. PMID 23457163.

- ^ "Why is smoking addictive?". NHS Choices. 29 Aralık 2011. 2 Kasım 2015 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 29 Kasım 2013.

- ^ Smith, Barbara K. Timby, Nancy E. (2005). Essentials of nursing : care of adults and children. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. s. 338. ISBN 978-0-7817-5098-1.

- ^ Rom, William N.; Markowitz, Steven B., (Ed.) (2007). Environmental and occupational medicine (4th bas.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ss. 521–2. ISBN 978-0-7817-6299-1.

- ^ "Wet cutting". Health and Safety Executive. 25 Eylül 2015 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: November 29, 2013.

- ^ George, Ronald B. (2005). Chest medicine : essentials of pulmonary and critical care medicine (5th bas.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. s. 172. ISBN 978-0-7817-5273-2.

- ^ a b Vestbo, Jørgen (2013). "Management of Stable COPD". Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (PDF). Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. ss. 31–8.

- ^ a b Drummond MB, Dasenbrook EC, Pitz MW, Murphy DJ, Fan E (November 2008). "Inhaled corticosteroids in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 300 (20). ss. 2407–16. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.717. PMID 19033591.

- ^ a b Carlucci A, Guerrieri A, Nava S (December 2012). "Palliative care in COPD patients: is it only an end-of-life issue?". Eur Respir Rev. 21 (126). ss. 347–54. doi:10.1183/09059180.00001512. PMID 23204123.

- ^ "COPD — Treatment". U.S. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. 27 Nisan 2012 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 2013-07-23.

- ^ Puhan MA, Gimeno-Santos E, Scharplatz M, Troosters T, Walters EH, Steurer J (2011). Puhan, Milo A (Ed.). "Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 10. ss. CD005305. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005305.pub3. PMID 21975749.

- ^ Lacasse Y, Goldstein R, Lasserson TJ, Martin S (2006). Lacasse, Yves (Ed.). "Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 4. ss. CD003793. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub2. PMID 17054186.

- ^ Ferreira IM, Brooks D, White J, Goldstein R (2012). Ferreira, Ivone M (Ed.). "Nutritional supplementation for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 12. ss. CD000998. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000998.pub3. PMID 23235577.

- ^ van Dijk WD, van den Bemt L, van Weel C (2013). "Megatrials for bronchodilators in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) treatment: time to reflect". J Am Board Fam Med. 26 (2). ss. 221–4. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2013.02.110342. PMID 23471939.

- ^ Liesker JJ, Wijkstra PJ, Ten Hacken NH, Koëter GH, Postma DS, Kerstjens HA (February 2002). "A systematic review of the effects of bronchodilators on exercise capacity in patients with COPD". Chest. 121 (2). ss. 597–608. doi:10.1378/chest.121.2.597. PMID 11834677.

- ^ Chong J, Karner C, Poole P (2012). Chong, Jimmy (Ed.). "Tiotropium versus long-acting beta-agonists for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 9. ss. CD009157. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009157.pub2. PMID 22972134.

- ^ a b Karner C, Cates CJ (2012). Karner, Charlotta (Ed.). "Long-acting beta(2)-agonist in addition to tiotropium versus either tiotropium or long-acting beta(2)-agonist alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 4. ss. CD008989. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008989.pub2. PMID 22513969. Kaynak hatası: Geçersiz

<ref>etiketi: "Karner2012" adı farklı içerikte birden fazla tanımlanmış (Bkz: Kaynak gösterme) - ^ a b c d e f g h Vestbo, Jørgen (2013). "Therapeutic Options" (PDF). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. ss. 19–30.

- ^ a b Cave, AC.; Hurst, MM. (May 2011). "The use of long acting β₂-agonists, alone or in combination with inhaled corticosteroids, in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a risk-benefit analysis". Pharmacol Ther. 130 (2). ss. 114–43. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.12.008. PMID 21276815.

- ^ Spencer, S; Karner, C; Cates, CJ; Evans, DJ (Dec 7, 2011). Spencer, Sally (Ed.). "Inhaled corticosteroids versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 12. ss. CD007033. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007033.pub3. PMID 22161409.

- ^ Wang, J; Nie, B; Xiong, W; Xu, Y (April 2012). "Effect of long-acting beta-agonists on the frequency of COPD exacerbations: a meta-analysis". Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics. 37 (2). ss. 204–11. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01285.x. PMID 21740451.

- ^ Decramer ML, Hanania NA, Lötvall JO, Yawn BP (2013). "The safety of long-acting β2-agonists in the treatment of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. Cilt 8. ss. 53–64. doi:10.2147/COPD.S39018. PMC 3558319 $2. PMID 23378756.

- ^ Nannini, LJ; Lasserson, TJ; Poole, P (Sep 12, 2012). Nannini, Luis Javier (Ed.). "Combined corticosteroid and long-acting beta(2)-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta(2)-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 9. ss. CD006829. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006829.pub2. PMID 22972099.

- ^ Cheyne L, Irvin-Sellers MJ, White J (Sep 16, 2013). Cheyne, Leanne (Ed.). "Tiotropium versus ipratropium bromide for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9). ss. CD009552. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009552.pub2. PMID 24043433.

- ^ Karner, C; Chong, J; Poole, P (Jul 11, 2012). Karner, Charlotta (Ed.). "Tiotropium versus placebo for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 7. ss. CD009285. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009285.pub2. PMID 22786525.

- ^ Singh S, Loke YK, Furberg CD (September 2008). "Inhaled anticholinergics and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 300 (12). ss. 1439–50. doi:10.1001/jama.300.12.1439. PMID 18812535.

- ^ Singh S, Loke YK, Enright P, Furberg CD (January 2013). "Pro-arrhythmic and pro-ischaemic effects of inhaled anticholinergic medications". Thorax. 68 (1). ss. 114–6. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201275. PMID 22764216.

- ^ Jones, P (Apr 2013). "Aclidinium bromide twice daily for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review". Advances in therapy. 30 (4). ss. 354–68. doi:10.1007/s12325-013-0019-2. PMID 23553509.

- ^ Cazzola, M; Page, CP; Matera, MG (Jun 2013). "Aclidinium bromide for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 14 (9). ss. 1205–14. doi:10.1517/14656566.2013.789021. PMID 23566013.

- ^ Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Carson SS, Lohr KN (2006). "Efficacy and Safety of Inhaled Corticosteroids in Patients With COPD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Health Outcomes". Ann Fam Med. 4 (3). ss. 253–62. doi:10.1370/afm.517. PMC 1479432 $2. PMID 16735528.

- ^ Shafazand S (June 2013). "ACP Journal Club. Review: inhaled medications vary substantively in their effects on mortality in COPD". Ann. Intern. Med. 158 (12). ss. JC2. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-12-201306180-02002. PMID 23778926.

- ^ Mammen MJ, Sethi S (2012). "Macrolide therapy for the prevention of acute exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 122 (1–2). ss. 54–9. PMID 22353707.

- ^ a b Herath, SC; Poole, P (Nov 28, 2013). "Prophylactic antibiotic therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 11. ss. CD009764. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009764.pub2. PMID 24288145.

- ^ Simoens, S; Laekeman, G; Decramer, M (May 2013). "Preventing COPD exacerbations with macrolides: a review and budget impact analysis". Respiratory medicine. 107 (5). ss. 637–48. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2012.12.019. PMID 23352223.

- ^ Barr RG, Rowe BH, Camargo CA (2003). Barr, R Graham (Ed.). "Methylxanthines for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2. ss. CD002168. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002168. PMID 12804425.

- ^ a b COPD Working, Group (2012). "Long-term oxygen therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an evidence-based analysis". Ontario health technology assessment series. 12 (7). ss. 1–64. PMC 3384376 $2. PMID 23074435.

- ^ Bradley JM, O'Neill B (2005). Bradley, Judy M (Ed.). "Short-term ambulatory oxygen for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 4. ss. CD004356. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004356.pub3. PMID 16235359.

- ^ Uronis H, McCrory DC, Samsa G, Currow D, Abernethy A (2011). Abernethy, Amy (Ed.). "Symptomatic oxygen for non-hypoxaemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 6. ss. CD006429. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006429.pub2. PMID 21678356.

- ^ Chapman, Stephen (2009). Oxford handbook of respiratory medicine (2nd bas.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. s. 707. ISBN 978-0-19-954516-2.

- ^ Blackler, Laura (2007). Managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. s. 49. ISBN 978-0-470-51798-7.

- ^ Jindal, Surinder K (2013). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Jaypee Brothers Medical. s. 139. ISBN 978-93-5090-353-7.

- ^ a b O'Driscoll, BR; Howard, LS; Davison, AG; British Thoracic, Society (October 2008). "BTS guideline for emergency oxygen use in adult patients". Thorax. 63 (Suppl 6). ss. vi1–68. doi:10.1136/thx.2008.102947. PMID 18838559.

- ^ Walters, JA; Tan, DJ; White, CJ; Gibson, PG; Wood-Baker, R; Walters, EH (September 2014). "Systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 9. ss. CD001288. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001288.pub4. PMID 25178099.

- ^ Walters, JA; Tan, DJ; White, CJ; Wood-Baker, R (10 December 2014). "Different durations of corticosteroid therapy for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Cilt 12. ss. CD006897. PMID 25491891.

- ^ a b Vollenweider DJ, Jarrett H, Steurer-Stey CA, Garcia-Aymerich J, Puhan MA (2012). Vollenweider, Daniela J (Ed.). "Antibiotics for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 12. ss. CD010257. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010257. PMID 23235687.

- ^ Jeppesen, E; Brurberg, KG; Vist, GE; Wedzicha, JA; Wright, JJ; Greenstone, M; Walters, JA (May 16, 2012). "Hospital at home for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Cilt 5. ss. CD003573. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003573.pub2. PMID 22592692.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. 11 Şubat 2014 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: Nov 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA; ve diğerleri. (December 2012). "Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859). ss. 2197–223. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. PMID 23245608.

- ^ a b Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V; ve diğerleri. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859). ss. 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMID 23245607.

- ^ Medicine, prepared by the Department of Medicine, Washington University School of (2009). The Washington manual general internal medicine subspecialty consult (2nd bas.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. s. 96. ISBN 978-0-7817-9155-7.

- ^ "Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Fact sheet N°315". WHO. November 2012. 2 Temmuz 2015 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R; ve diğerleri. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859). ss. 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

- ^ Rycroft CE, Heyes A, Lanza L, Becker K (2012). "Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a literature review". Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. Cilt 7. ss. 457–94. doi:10.2147/COPD.S32330. PMC 3422122 $2. PMID 22927753.

- ^ Simpson CR, Hippisley-Cox J, Sheikh A (2010). "Trends in the epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in England: a national study of 51 804 patients". Brit J Gen Pract. 60 (576). ss. 483–8. doi:10.3399/bjgp10X514729. PMC 2894402 $2. PMID 20594429.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Nov 23, 2012). "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among Adults — United States, 2011". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 61 (46). ss. 938–43. PMID 23169314.

- ^ "Morbidity & Mortality: 2009 Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases" (PDF). National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 19 Ekim 2013 tarihinde kaynağından (PDF) arşivlendi.

- ^ a b Torio CM, Andrews RM (2006). "National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011: Statistical Brief #160". Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. PMID 24199255.

- ^ "Emphysema". Dictionary.com. 13 Haziran 2015 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b Ziment, Irwin (1991). "History of the Treatment of Chronic Bronchitis". Respiration. 58 (Suppl 1). ss. 37–42. doi:10.1159/000195969. PMID 1925077.

- ^ a b c d Petty TL (2006). "The history of COPD". Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 1 (1). ss. 3–14. doi:10.2147/copd.2006.1.1.3. PMC 2706597 $2. PMID 18046898.

- ^ a b Wright, Joanne L.; Churg, Andrew (2008). "Pathologic Features of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Diagnostic Criteria and Differential Diagnosis" (PDF). Fishman, Alfred; Elias, Jack; Fishman, Jay; Grippi, Michael; Senior, Robert; Pack, Allan (Ed.). Fishman's Pulmonary Diseases and Disorders (4th bas.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ss. 693–705. ISBN 978-0-07-164109-8.

- ^ George L. Waldbott (1965). A struggle with Titans. Carlton Press. s. 6.

- ^ Fishman AP (May 2005). "One hundred years of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 171 (9). ss. 941–8. doi:10.1164/rccm.200412-1685OE. PMID 15849329.

- ^ Yuh-Chin, T. Huang (2012-10-28). A clinical guide to occupational and environmental lung diseases. [New York]: Humana Press. s. 266. ISBN 978-1-62703-149-3.

- ^ "Pink Puffer - definition of Pink Puffer in the Medical dictionary - by the Free Online Medical Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com. Erişim tarihi: 2013-07-23.

- ^ a b c Weinberger, Steven E. (2013-05-08). Principles of pulmonary medicine (6th bas.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders. s. 165. ISBN 978-1-62703-149-3.

- ^ Des Jardins, Terry (2013). Clinical Manifestations & Assessment of Respiratory Disease (6th bas.). Elsevier Health Sciences. s. 176. ISBN 978-0-323-27749-5.

- ^ An outcomes strategy for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma in England (PDF). Department of Health. 18 July 2011. s. 5. Erişim tarihi: 27 November 2013.

- ^ Bloom, D (2011). The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases (PDF). World Economic Forum. s. 24.

- ^ Nici, Linda (2011). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Co-Morbidities and Systemic Consequences. Springer. s. 78. ISBN 978-1-60761-673-3.

- ^ Inamdar, AC; Inamdar, AA (Oct 2013). "Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in lung disorders: pathogenesis of lung diseases and mechanism of action of mesenchymal stem cell". Experimental lung research. 39 (8). ss. 315–27. doi:10.3109/01902148.2013.816803. PMID 23992090.

- ^ Conese, M; Piro, D; Carbone, A; Castellani, S; Di Gioia, S (2014). "Hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of chronic respiratory diseases: role of plasticity and heterogeneity". TheScientificWorldJournal. Cilt 2014. s. 859817. doi:10.1155/2014/859817. PMC 3916026 $2. PMID 24563632.

- ^ Akers, R. Michael; Denbow, D. Michael (2008). Anatomy and Physiology of Domestic Animals. Arnes, AI: Wiley. s. 852. ISBN 978-1-118-70115-7.

- ^ Wright, JL; Churg, A (December 2002). "Animal models of cigarette smoke-induced COPD". Chest. 122 (6 Suppl). ss. 301S–6S. doi:10.1378/chest.122.6_suppl.301S. PMID 12475805.

- ^ Churg, A; Wright, JL (2007). "Animal models of cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive lung disease". Contributions to microbiology. Contributions to Microbiology. Cilt 14. ss. 113–25. doi:10.1159/000107058. ISBN 3-8055-8332-X. PMID 17684336.

- ^ Marinkovic D, Aleksic-Kovacevic S, Plamenac P (2007). "Cellular basis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in horses". Int. Rev. Cytol. International Review of Cytology. Cilt 257. ss. 213–47. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(07)57006-3. ISBN 978-0-12-373701-4. PMID 17280899.

- ^ Miller MS, Tilley LP, Smith FW (January 1989). "Cardiopulmonary disease in the geriatric dog and cat". Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 19 (1). ss. 87–102. PMID 2646821.

Dış bağlantılar

| Wikimedia Commons'ta Kronik obstrüktif akciğer hastalığı ile ilgili ortam dosyaları bulunmaktadır. |

- Curlie'de Kronik obstrüktif akciğer hastalığı (DMOZ tabanlı)

- Türk Toraks Derneği

| Wikimedia Commons'ta Kronik obstrüktif akciğer hastalığı ile ilgili ortam dosyaları bulunmaktadır. |